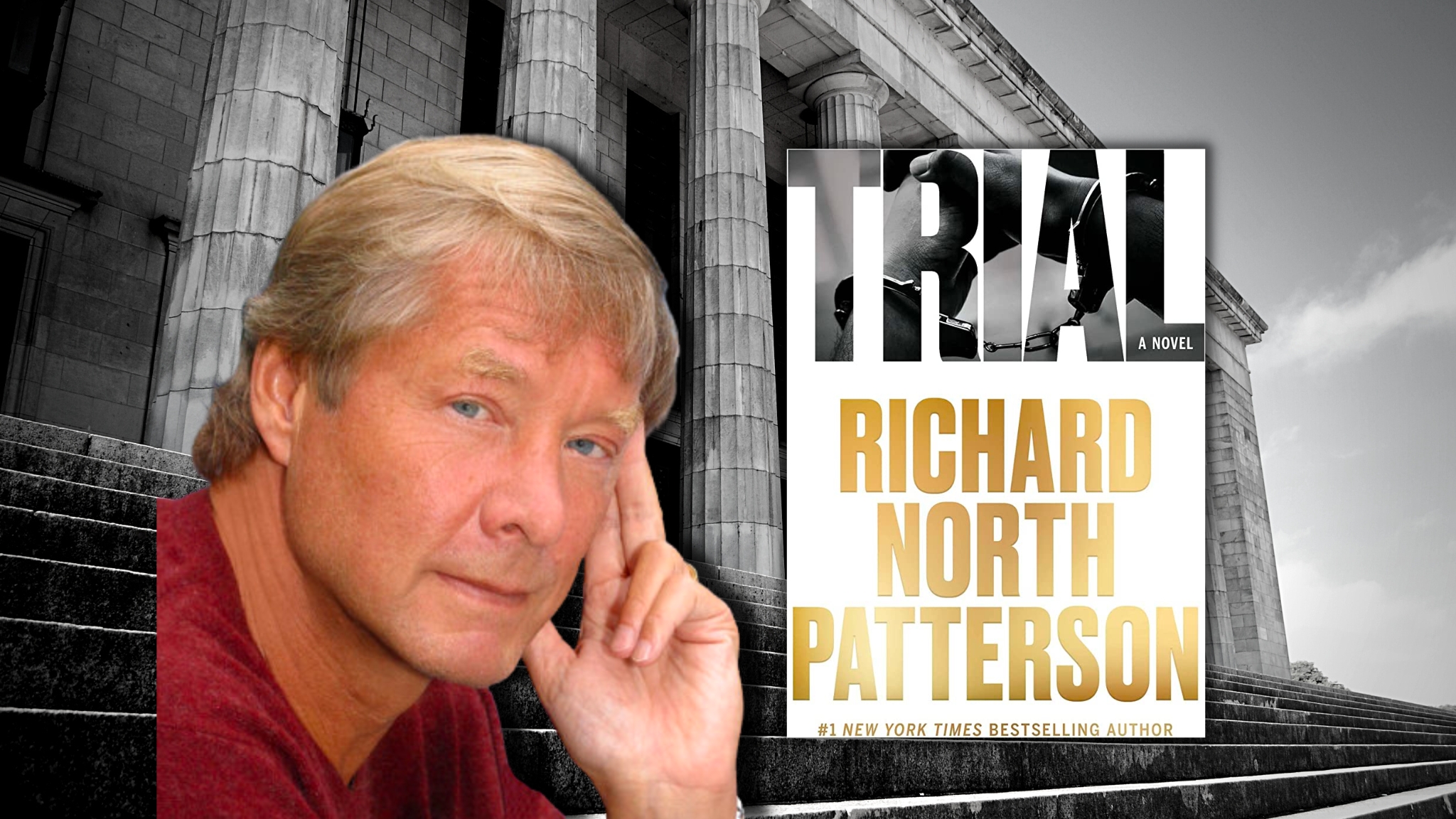

If bestselling author Richard North Patterson can’t get his fast-paced legal thriller focusing on American racism published in New York, then who can?

Patterson, who has written 22 novels, been on the NYT bestseller list 16 times and sold more than 25 million books, should have his pick among publishers. Instead, he couldn’t find anyone in Manhattan to handle his gripping new suspense novel Trial. Just about everyone agreed it’s a very good novel, but they fear the American Dirt syndrome, and he says they quietly told him white authors can’t write about the Black experience of racism in America.

At a time when writers are being threatened by calls for book banning all across America based on race and sex, 19 New York publishers did just that, Patterson says.

“My agents warned me that I was asking for trouble with major publishers, and I was acutely aware of the risk — most famously exemplified in 2020, when Jeanine Cummins, the white author of American Dirt, was widely castigated for the way she depicted a Mexican mother and son struggling to cross the U.S. border. As the British novelist Zadie Smith observed in 2019, ‘The old — and never especially helpful — adage ‘write what you know’ has morphed into something more like a threat: ‘Stay in your lane,’” he wrote in a column in The Wall Street Journal, which has received much attention.

“To license the imagination across racial lines,” he says, “is not the enemy of diversity of authorship. Rather, we should directly confront the woeful lack of diversity in publishing houses and, even today, among authors.”

That said, Patterson’s account of racism, Black voter suppression, and an inter-racial love affair in America set in 2022 will start showing up on bookshelves June 13—but from an unexpected source. Ironically, a small conservative and Christian publisher, Post Hill Press, has taken up the cause. When New York publishers shied away from this novel, Post Hill Press Executive Editor Adam Bellow didn’t hesitate. A 30-year veteran of New York publishing and son of acclaimed bestselling novelist Saul Bellow, Adam saw a huge business opportunity. Trial has bestseller written all over it.

“It’s astonishing to me that a book by a prominent liberal author on a political topic of pressing interest to liberals can only be published by a conservative,” Bellow says. “…I’m a well-known conservative who disagrees with Ric on issues like voter suppression, but it turns out I’m a lot more of a liberal than the mainstream publishers who passed on his book.”

Post Hill Press is headquartered on the outskirts of Nashville, Tennessee, in Brentwood, certainly no backwater, but it’s not exactly the center of the publishing world nestled among the country music stars.

“Not once did anyone suggest that any aspect of the manuscript was racially insensitive or obtuse,” Patterson wrote in his Journal piece. “Rather, the seemingly dominant sentiment was that only those personally subject to discrimination could be safely allowed to depict it through fictional characters.”

Refusal to publish his novel was so efficient, Patterson notes, it took only four months for all 19 of his New York rejections to fall into line like cascading dominoes. And just who shied away? “Pretty much anybody you can think of, including Hatchette imprints (which published his last novel nine years ago) …It basically breaks publishing into ethnic neighborhoods … Most of the people who said you can’t write this are white people who live in Manhattan.”

“For these publishers to imagine themselves the literary benefactors of Black America bespeaks of self-flattering and lamentably unexamined condescension,” Patterson told the website Bulwark, which he writes for on occasion.

What they are doing, he says, is committing literary apartheid — the cousin of book banning. “It’s kind of a misplaced notion of affirmative action.”

“A number of them found it (Trial) impressive; several opined that it evoked my best work. Nonetheless, my ethnicity was now deeply problematic,” Patterson said in the Journal.

Why is the publishing industry so afraid to take this on?

“It’s two things,” Patterson says. “It’s fear of self-righteous young people and fear of Twitter mobs.”

“The upshot,” Bellow says, “is the young people are in charge. What it means is writers are going to have to conform to the new standard. It will be fine if they are not white men … There’s a level of organized, idealizing activism within these publishing companies. At the managerial level, there’s a kind of cowardly abandonment of leadership and authority. The leadership when I was coming up would never allow the young people to determine which books were being published.”

Which is exactly what one publisher told Patterson. He said he liked the novel but would have to check first with his younger staff.

“This person knew perfectly well what the young people would say,” Bellow says. “They said, ‘no, it’s not allowed.’ It’s called cultural appropriation … It’s young people in their 20s — marketing associates, junior this and junior that.”

Patterson, who is a lawyer, says he has no desire to take on the role of aggrieved white man. Rather, he believes the publishing industry is woefully lacking in diversity. “But to repress books based principally on authorial identity is inimical to the language of creativity, not to mention to the spirit of a pluralist democracy.”

And what does this mean for other thriller, mystery, and suspense writers — those who have never visited the bestseller list or are struggling to get their first novel published? There are a lot of writers who are stretching the limits and taking chances right now who don’t fit the current trend in publishing, Bellows says. Now they are openly being discouraged from even trying. Patterson fears many may never get their writing careers off the ground.

“It’s not just affecting Ric,” Bellow says. “It’s affecting many people. It’s a trend that’s been going on over a long time. We’ve got writers coming to us (small press) from all perspectives … I see this as a very serious situation. It’s not a joke. As an independent publisher, however, it’s benefiting me.”

“Last year there was little resistance from writers themselves,” he says. “We have to see writers stand up and say ‘no.’”

Patterson, who describes himself as a liberal, has nothing but praise for his conservative publisher. “I give them credit for participating in something that is a matter of principal … They are due credit. I think the real embarrassment belongs to mainstream publishing. I just don’t mean me. This idea of creative segregation is … bad for everyone.”

Bellow notes he and Patterson are miles apart on ideology. “I don’t agree with him, but that’s the point of being a publisher. You don’t have to agree with every book you publish. It’s not my point of view, but that doesn’t matter.”

If this were 1960, Patterson’s novel might have been called To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s been compared to Harper Lee’s classic. But this is 2023 and he has updated the story of racial prejudice focusing on how much has not changed in America since Lee’s breakout novel 63 years ago.

This tale of America’s original sin is played out through the entitled passion of a very rich and idealistic Massachusetts congressman who comes to understand even his privilege makes little difference when it comes to race. Patterson’s story shows us we are still fighting the same issues — many nuanced and layered by the decades — but still barely coagulating at the surface.

The story begins with the lust of the oh-so-very Boston-bred and white-privilege-sounding Chase Bancroft Brevard, an obvious choice for Harvard inbreeding. By contrast, Allie Hill is a young Black woman who found her place in the middle class because her family runs a Black funeral home in rural Georgia.

Approaching graduation at Harvard, Allie and Chase fall in love and struggle with the social differences between their upbringings. Their relationship grapples with not just two cultures colliding, but two entirely separate worlds. Patterson’s sensitive description of their relationship runs deep, and it alone is worth this thriller’s price of admission.

He explores class and race honestly. It’s disturbing to read and still we’re eager to know if two young college students can find common ground beyond the bedroom. When Allie abruptly leaves without a word at graduation time, they both return to their roots and ambitions — he to Boston and she to rural Georgia. He becomes a progressive lawyer and later the same breed of congressman. (What else is there in Massachusetts?) She takes up the cudgel of a Black voter registration organization to stop Georgia’s voter suppression efforts and becomes the state’s premier voting rights advocate.

They lose track of each other until one morning when Chase, a rising star in the Democratic Party, sees the woman who broke his heart on a cable news channel. He is shocked to learn she’s a single mother, and her only son has just been arrested and accused of murdering a white sheriff’s deputy. Chase quickly does the math and realizes the young high school senior is his.

Then the real trial begins as Patterson explores the relationships between a black woman and a white man — and their biracial son as they become a media sensation. Chase risks his political career going to Georgia to help his son only to realize how difficult that is — not only as a legal matter, but to be accepted as a father who’s missed out on his son’s entire existence.

Only then does the circus begin.

Their son’s murder trial attracts knuckle-dragging white supremacists protesting outside the courthouse. Patterson’s description is blunt and walks up to the edge of cartoonish. And yet, his writing captures that very truth, that white supremacists are cartoonish. Their exaggerated and incendiary spewing of intolerance, superiority and hate is comical but never benign.

“Too many white people are all tangled up about race — they’re angry about feeling subliminal guilt without knowing enough about our history to understand why,” says protagonist Chase. “Instead, they feel resentful and, in an odd way, victimized. A classic case of projection.”

The underlying subtlety of today’s racism versus the sensational chanting of white supremacists displays the racial flashpoint in Patterson’s story. It’s easier for the frothing news media at the trial to tell the story of hate-spewing racists with guns and camouflage, than it is to assimilate the vital nuances of America’s racial divide into a cohesive relatable story. Journalism has its limits, but Patterson’s fiction does not.

Perhaps the novel’s most important element is Patterson’s examination of the turmoil of falling in love with someone of a different race in a country where many still refused to accept those relationships and are fearful to acknowledge we are not all of one genre. His writing is precise as he examines in detail their feelings for each other. Rarely, do you find a suspense thriller with this degree of literary depth.

He then steps beyond their relationship and examines today’s Black and white environment — two separate American cultures that do not live in harmony but side-by-side like two roommates who tolerate each other because neither can afford the apartment without the other. Patterson captures it in its full ugliness while never slowing the pace of his engrossing story.

How did he manage this? He spent a lot of time researching his topic. Patterson hasn’t written a novel for nearly a decade because he spent that time writing political commentary for HuffPost, The Bulwark and The Boston Globe. He realized much of his writings dealt with race, so he decided to use the creative reserves of fiction to delve more intensely into racism and capture its intrinsic truths.

“To depict my fictional Cade County, I spent an extended period in Sumter County, Georgia, a jurisdiction with a complicated past and present marked by often bitter political and social divisions,” Patterson says. Sumter is near Americus, Georgia, near former President Jimmy Carter’s home. There, Patterson interviewed grassroots voting rights activists, community leaders, ministers, civil rights lawyers, Black and white politicians, judges, the first Black sheriff, and a woman who, in 1960 at age 11, was imprisoned with other adolescent girls who tried to integrate a movie theater — an event known as the Leesburg Incident. Patterson includes it in his stunning narrative.

While in Sumter County he toured both Black and white cemeteries. The white cemetery was well-groomed and filled with Confederate statues. The Black cemetery was not nearly as pristine. Patterson noticed rows of infant graves there and was told infant mortality in rural Georgia is much higher among Blacks than whites — the result of their lack of access to good healthcare.

“You just see it all. It’s just not subtle,” he says.

To portray Allie Hill accurately, Patterson interviewed Nse Ufot, successor to Stacey Abrams as the head of the state’s seminal voting rights organization, the New Georgia Project, and three Black women who attended Harvard in 2003.

“This is a portrait of the America I know,” says Bruce Gordon, former CEO of the NAACP. “It is compelling, contemporary, and thoughtfully researched truth-telling. Trial might be fictional, but it is real.”

As real as Patterson’s fight to get his novel published.