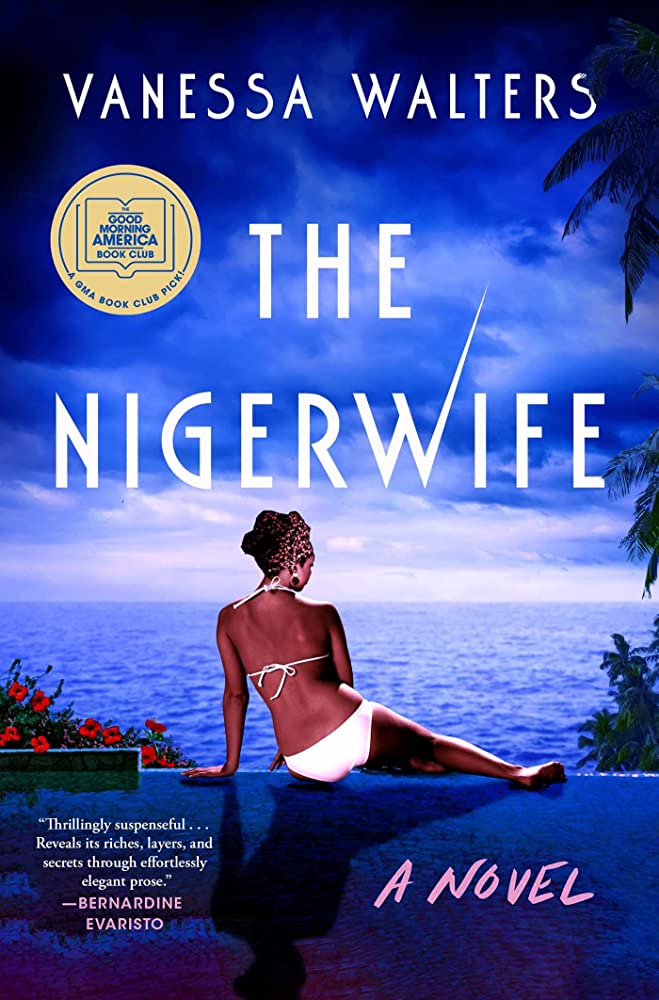

The Nigerwife by Vanessa Walters

With The Nigerwife, novelist, playwright and poet Vanessa Walters takes her first excursion into the mystery genre — and it’s an impressive one. The book has already been optioned for HBO.

The Nigerwife introduces us to Nicole, who seemingly has the perfect life — a handsome husband, Tonye, two beautiful kids, plenty of money, servants… It’s quite a different world from her former life in London. However, she lives under the thumb of her parents-in-law who call all the shots.

Then one day, Nicole disappears.

Her estranged aunt, Claudine, flies in from London to try and find out what has happened to Nicole — and is shocked to discover that not only does Nicole’s new family not seem to care about what happened to her, neither do the police. The focus seems to be on planning the celebrity wedding of one of Tonye’s sisters.

The Nigerwife is a remarkable novel with family relationships at its heart, and Lagos is the perfect setting for this strangely twisted story. In this interview for The Big Thrill, Walters tells us a bit more about what inspired the book, the role location played in her writing process, and what she hopes readers take away from this story.

Would you start off by telling us a bit about yourself and what drew you to write this novel?

I was also a Nigerwife, part of the community of Nigerwives, living in Lagos with my husband and two boys. Although I had seven wonderful years in Lagos, I also struggled with dislocation and a lack of purpose and identity there. At times, I felt I’d disappeared. I sometimes wondered, what if I actually disappeared? And thus, a story was born about a fictional Nigerwife with all these issues, like myself, in a dramatic fictional story replete with characters. It was an easy story to write.

You clearly know Lagos well, and you say that Lagos is “everyone’s antagonist.” Would you expand on that?

Lagos is an addictively compelling city but not the easiest to navigate. It has all the allure of a “capital” city (no longer the actual capital) but lacks the necessary infrastructure. It’s also a competitive and dense place to live with over 20 million inhabitants. Meanwhile the paths to building wealth are often blocked by class or cultural hurdles and the city literally often becomes impassable (traffic, lack of transport, insecurity, power cuts, flooding, dust storms, lack of information). Finally, it’s a religious city, which by Western standards can seem rigidly narrow-minded, particularly in regard to sexuality, gender conformity, and comportment. All of this can make it feel like the city itself is against you, a siren that draws you in only to dash you on its pitiless rocks.

The novel has two protagonists — Nicole and Claudine. Each tells the story: Nicole from before her disappearance and Claudine from after it. Yet we learn Claudine’s story as well. Why did you choose this particular structure for the novel?

Our fates are generations in the making and I wanted to show this from Claudine’s perspective. She is literally the backstory to Nicole’s predicament, walking into the novel and revealing the history of this family and character.

Tonye’s family is ruled by his father, known simply as Chief. Everyone defers to him, and the women have hardly any say. Is this a particular example for the story or would you say in general that Nigeria has a patriarchal culture? Is the Nigerwives Association a support mechanism to try to counter that?

As a young British Jamaican woman growing up in London, I always had a lot to say and never felt significantly censored or hemmed in by the British or Caribbean culture there — even though the English are known to be relatively reserved. On the contrary, I was encouraged to speak out. But in Lagos, I noticed many differences. Seniority is revered in Nigeria, so young people are often silenced. Class structures also impact who gets heard. I also observed that women were often expected to defer to male authority. In The Nigerwife, I wanted to explore the impact of such silencing on people. The Nigerwives Association continues to represent a safe space for foreign women to express themselves without fear of offending their in-laws. Regardless of class or background, they get to let off steam and be themselves. That was important for me, and it can be a lifesaver for some Nigerwives like Nicole.

Claudine was born in Jamaica, and after many years her mother brought her to England but showed her little affection. Both Nicole and Claudine had fraught relationships with their parents. Is that the basis of at least some of the difficulties they experience as adults?

I have done quite a lot of research on Jamaican culture — as well as having two Jamaican parents myself — and I noticed similar, if less severe, issues to those expressed in the novel. Slavery and the post-slavery hardships faced by most Black Jamaicans continue to wreak havoc on Jamaican communities. Deliberate underinvestment in and continued racially biased exploitation of Jamaica has meant that Jamaicans have often had to leave the island to seek advancement or resources resulting in a fracturing of family and sense of self. Claudine’s feeling of loneliness is a direct result of her parents leaving her behind in Jamaica as a child and not bonding with her. As an adult, she has issues forming positive relationships, and history repeats itself, with Nicole also feeling abandoned. Nicole then, in a sense, feels abandoned within her marriage and this leads to certain actions she takes in the novel. It becomes a cycle of generational trauma that Claudine becomes keen to end.

There are plenty of suspects in Nicole’s disappearance — not because their motives are particularly strong but rather because it seems so easy to get away with murder in Lagos. This keeps the reader guessing through the book. Did you plan it that way, or did it develop with the story?

The story developed over time, but the body at the beginning of the story was inspired by real life. I occasionally saw bodies pass along the Lagoon and wondered at the fact there was no fuss about it — no call to the police, and I never saw them picked up even though they festered for hours on a busy shipping lane and many people saw them. The Lagos police are not unique in the world for being vulnerable to corrupt elements. However, a lack of resources, inadequate pay, and housing (corrupt officials often steal their budgets) affect their ability and willingness to provide justice.

Do you have other projects underway? If so, would you tell us a bit about them?

I’m very excited about the current HBO development of The Nigerwife. I’m waiting to see what happens next with that. I’m also working on my second novel, which is set in America but explores similar themes of marriage, family, self-worth and identity. I seem to have endless questions on these topics.

—

This story appears through BookTrib’s partnership with the International Thriller Writers. It first appeared in The Big Thrill.

About Vanessa Walters:

About Vanessa Walters:

Vanessa Walters was born and raised in London and has a background in international journalism and playwriting and is a Tin House resident and a Millay Colony resident. She is the author of two previous YA books and The Nigerwife. She currently lives in Brooklyn.