The curious case of John Banville versus his alter ego, Benjamin Black …

The man writes perfect sentences. Of this, it’s difficult to dispute. There’s a reason there is perennial chatter about him winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. That hasn’t happened yet, but odds are he will win within the decade.

Over the course of fifty years, John Banville has penned 29 books. Eighteen of those carry his own name as the proclaimed author. The other eleven carry the name Benjamin Black. It’s his crime writer’s never-secret pen name. The two scribes wrote distinctly different fiction — until last fall, when Banville chose, curiously, to publish the Black novel Snow (Hanover Square Press) under his own name.

Upon release in October, The New York Times asked him why. His answer was less than forthcoming. He called Benjamin Black “a rascal” that he no longer needed. He claimed to have shut his darker half in a room “with a pistol, a phial of sleeping pills, and a bottle of Scotch.” A fine bit of noir imagery, yet the article shed little light. Perhaps he didn’t really know himself why Black needed burying.

Or maybe he knew the truth: Benjamin Black writes better books, and John Banville was growing a bit conflicted at this realization. And so, he published his latest crime novel under his God-given name, to set his literary canon straight. Ever conscious of his high-brow status (“Not that I think pretension necessarily a bad thing in a writer,” he told The Times), his rascally alter ego was becoming a bit troublesome.

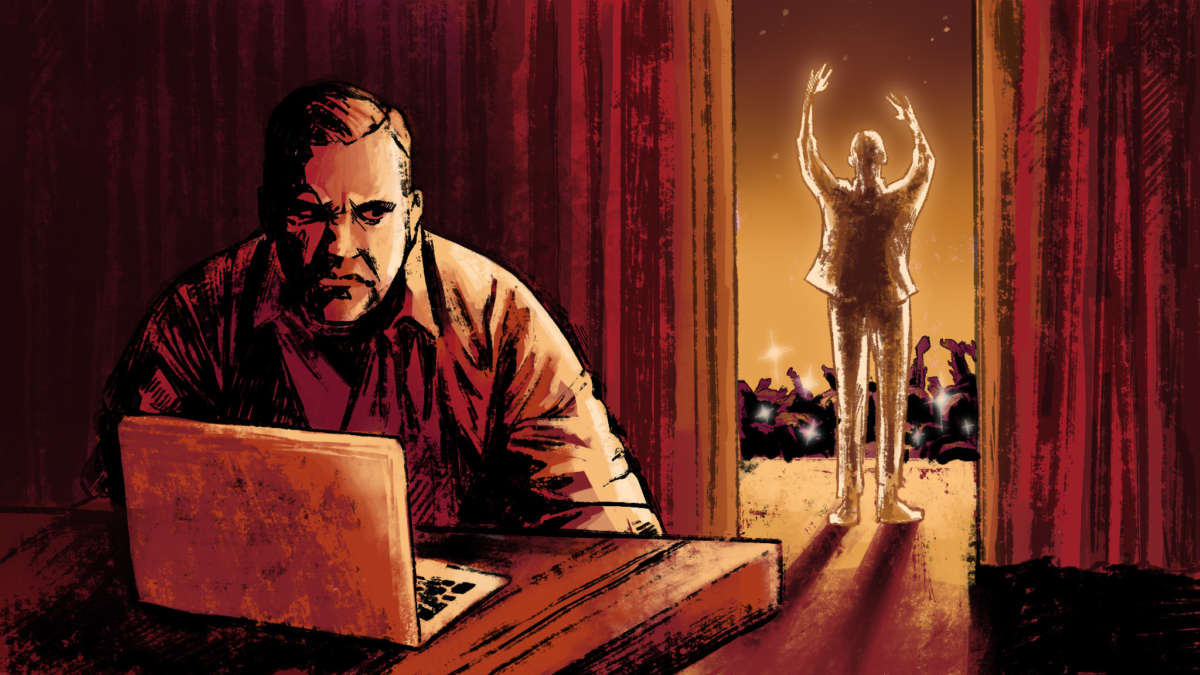

Pen names can be a beautiful thing. They can open an author to new genres. They can bestow freedom after acclaim has set its inevitable trap. Yet, there has seldom been a case where the pseudonym outstrips the celebrated author behind the curtain.

Since J.K. Rowling became the biggest seller this side of Shakespeare, she’s published five crime novels under the not-secret pen name of Robert Galbraith. These books are enjoyable. They’re competent if less than iconic. If she wasn’t J.K. Rowling, no editor alive would allow her latest entry in the series, Troubled Blood (Mulholland Books) to come in at close to 1,000 pages. But when you’ve made everyone in your publishing orbit so many gobs of money, you’ve earned the privilege to dispense with page counts. A tight plot without endless meandering — that’s for lesser genre writers to contend with.

Stephen King, no stranger to doorstop-thick, just-okay opuses has had his fun with pen names too. His eight Richard Bachman novels are a blast — particularly 2007’s Blaze (Scribner). Though no one’s comparing Bachman’s catalog to King’s, just as the Galbraith series is a minor league romp when compared to Rowling’s Harry Potter universe.

With John Banville, it’s all been turned upside down. Somehow his pen name became mightier than the man’s — which isn’t to discount Banville’s brilliant writing under his own name. He did, after all, win the Booker Prize for his novel The Sea (Knopf). It’s just that his “own” novels tend to be rather plotless and plodding, albeit with those perfect beautiful sentences. They’re difficult. One can almost hear the professor at the front of the classroom: This, my students, is Literature. This, ladies and gentlemen, is a Sentence … The professor isn’t wrong. Nor is he much fun.

However, fifteen years ago, beginning with the novel Christine Falls (Henry Holt) in 2006, John Banville decided to start enjoying himself. He turned to crime novels and the words flowed so fast that he thought of himself as a “slut” as the pages poured out of him. The thing is, the Sentences — with the capital “S” — came along for the ride.

He proceeded to churn out seven books featuring Quirke, the ill-tempered 1950s Dublin pathologist, along with four Black-penned books outside the series. All were supreme literary fun. Benjamin Black, that wanton alter ego, managed to have the best of both worlds. A genre writer with Nobel-worthy chops — who’d have thought? Well, Raymond Chandler, for one, which might be a reason the Chandler estate reached out to Mr. Black and asked him to resurrect the ultimate high-lit private eye, Philip Marlowe. Black obliged and delivered 2015’s excellent The Black-Eyed Blonde (Henry Holt).

With his latest novel, Snow, it’s almost as though Banville felt a bit defensive about the “rascal” topping the esteemed man of letters. Why else would he put his own name on the cover? The book fits snuggly within the world created by Benjamin Black. Dr. Quirke is even referenced in the early pages. His friend and sometime partner, Inspector Hackett, is a constant presence. Hackett is now the Chief Superintendent of the Dublin police force. Snow‘s protagonist, St. John (pronounced Sinjin) Strafford reports to him. Detective Strafford is assigned to investigate a gruesome murder at a grand country pile in County Wexford. Everyone at the estate is a suspect. The body is even discovered in the Library. Every genre cliché is playfully in play and everyone appears to be in on the joke.

This isn’t a standalone literary John Banville novel in any sense. It’s a Benjamin Black crime novel: set in 1950s Ireland, featuring horrible priests, bleak landscapes, self-loathing characters, and the most disturbing of secrets. (This may sound like a stew of downers, but the best crime writers often make human misery a joy to read … )

Why is his creator suddenly seizing the stage? Is it because Mr. Hyde has become more interesting than Dr. Jekyll? Did the Great and Powerful Oz/Banville feel the need to clarify identities for posterity?

Clearly, this goes to the still-unfortunate bookstore ghetto where mystery and crime fiction find themselves. One would have thought those false barriers were stripped away years ago. Yet even someone with a literary rep as rock-solid as Banville’s seemed to find it necessary to clarify where his latest work ought to be classified.

Perhaps, when he does win his well-deserved Nobel someday, he’ll thank that rascal, Benjamin Black, for bringing out his very best.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/440px-John_Banville_2019_III-2.jpg

About John Banville:

John Banville was born in Wexford, Ireland, in 1945, the youngest of three siblings. He was educated at Christian Brothers schools and St Peter’s College, Wexford. He was a journalist for 30 years, beginning with The Irish Press as a sub-editor in 1969 and eventually becoming the Literary Editor at The Irish Times from 1988 to 1999. John’s first book, Long Lankin, a collection of short stories and a novella, was published in 1970. Since then he has published numerous novels and his work has been collected in the anthology, Possessed of a Past: A John Banville Reader.

Among the awards John’s novels have won are the Allied Irish Banks fiction prize, the American-Irish Foundation award, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, theGuardian Fiction Prize. In 1989 The Book of Evidence was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and was awarded the first Guinness Peat Aviation Award; in Italian, as La Spiegazione dei Fatti, the book was awarded the 1991 Premio Ennio Flaiano. Ghosts was shortlisted for the Whitbread Fiction Prize 1993; The Untouchable for the same prize in 1997. In 2003 John was awarded the Premio Nonino. He has also received a literary award from the Lannan Foundation in the US. In 2005, John won the Man Booker Prize for The Sea. In 2011 he was awarded the Franz Kafka Prize. Last year, John was awarded the Irish Pen Award for Outstanding Achievement in Irish Literature.