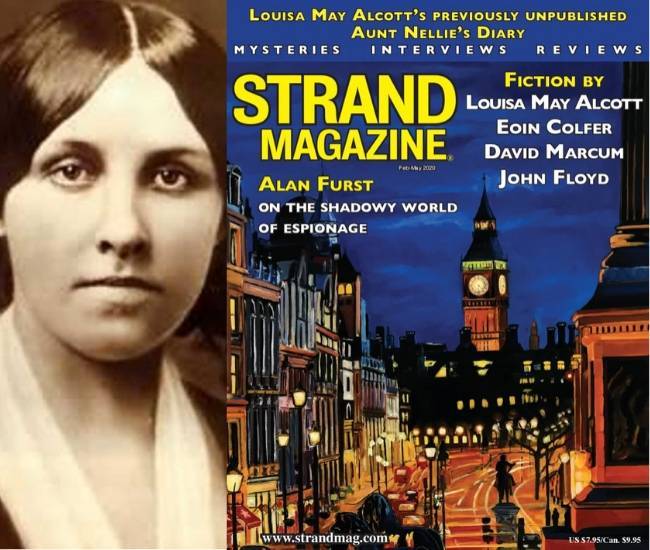

“Aunt Nellie’s Diary,” a newly discovered work by a teenaged Louisa May Alcott, has been published for the first time in the current issue of The Strand. The only problem? Alcott abandoned the story at a crucial moment, leaving the reader dangling with the final line, “I begged and prayed that she would …”

The story (and its origins) tantalizes fans of Little Women and Alcott scholars alike — as well as writers eager to try their hand at finishing the tale. (More on this in a bit.)

In his introduction to the story, Alcott scholar Professor Daniel Shealy says, “‘Aunt Nellie’s Diary’ … reveals the influences that sparked Alcott’s imagination and shows us an emerging talent on the cusp of a promising career at age 17.” She already had the mindset of a serious writer and understood how to create a page-turner, building the suspense to a big reveal. “Alcott, like any professional author, knew how to reach her reading audience,” Shealy writes.1

Andrew Gulli, managing editor of The Strand, discovered the story while searching the archives at the Houghton Library at Harvard University where a vast majority of Alcott’s papers are stored. Inspired by the recent success of Greta Gerwig’s film adaptation of Little Women, Gulli, a longtime fan of the book, felt there was more to Louisa’s writing. “I realized she was a very layered writer, complex and way ahead of her time,” he says.

Her life’s story contains many elements to which modern-day readers can relate. “Louisa May Alcott was a forerunner to the feminist movement,” says Gulli. “She was an abolitionist, and survived a spell working for an older man was creepy and harassed her several times.” Here Gulli is referring to incidents revealed in Alcott’s essay, “How I Went Out to Service,” written when she was 18.

A LOVE TRIANGLE BETWEEN A YOUNG MAN AND TWO TYPES OF BEAUTY

“Aunt Nellie’s Diary” hints at that complexity. The story is written as a diary, kept by a 40-year-old spinster (Nellie), who is caring for her teenage orphaned niece, Annie. Annie’s friend Isabel is visiting for the summer along with a family friend, Edward, who is recovering from an illness. A love triangle is established between the pure and ethereal Annie (resembling Louisa’s younger sister Lizzie, the inspiration for Beth March in Little Women), the worldly and glamorous Isabel, and the charming Edward, who vacillates between the two.

Alcott’s choice of language demonstrates her perceptions of beauty and its variations, showing a preference for Annie. Words such as quiet happiness, perfect inner stillness (bordering on the sacred), innocence and sweetness are used to describe Annie. Physically she is pale and slight. Isabel is vibrant and more physically beautiful, taking every opportunity to show it. But she is lacking that inner goodness, often acting petulant and demanding.

Alcott’s choice of language demonstrates her perceptions of beauty and its variations, showing a preference for Annie. Words such as quiet happiness, perfect inner stillness (bordering on the sacred), innocence and sweetness are used to describe Annie. Physically she is pale and slight. Isabel is vibrant and more physically beautiful, taking every opportunity to show it. But she is lacking that inner goodness, often acting petulant and demanding.

Jan Turnquist, executive director of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House noted a similarity between this story and a chapter from Little Women: “When the two girls are dressing to meet Aunt Nellie’s friends, Isabel is ‘in rich satin with pearls among the glossy braids of her dark hair … but Annie in simple white crepe with no ornaments save a little bouquet of violets and the quiet beauty of her own gentle face pleased me better.’ One can’t miss the similarity of ‘Meg goes to Vanity Fair’ in Little Women.”2

Several pages in, the story begins to take a dark turn with the introduction of the mysterious Mr. Ainslie who has a history with all three of the characters. Isabel and Annie are both upset at his arrival, which has disturbed Aunt Nellie. Annie is about to confide a shocking secret to her aunt when the story abruptly ends.

THE DARK, LURID SIDE OF LOUISA’S IMAGINATION

In the introduction, Daniel Shealy points out that Louisa was attracted to the darker side of life, confessing in her journal that she fancied “lurid things.”3 John Matteson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Eden’s Outcasts, commented that “even in this early work, we can see two conflicting impulses with which Alcott struggled long into her career. On the one hand, she wanted to tell stories that praise and reward kindness and virtue. At the same time, she loved indulging her dark side, expressing what she called her ‘lurid’ style. The angels and devils of her nature are plainly at war in ‘Aunt Nellie’s Diary’”4

Considering the life that Louisa was leading at the time the story was written, it is no wonder that her writing shows such contrast and complexity. Moody by nature with a deep-seated temper, Louisa endured constant upheaval due to her family’s poverty. Because of her father’s either unwillingness or inability to find paid work, the family was constantly struggling to get by.

In 1848, after living in bucolic Concord for three years, the Alcotts were suddenly uprooted to Boston where Mrs. Alcott became the breadwinner. Their living quarters, located in the slums, consisted of a grimy and cramped four-room basement apartment where Louisa was drafted to keep house. She described herself as a “caged seagull,” adding, “The bustle and dirt and change sent all lovely images and restful feelings away … I know God is always ready to hear, but heaven’s so far away in the city, and I so heavy I can’t fly out to find him.”5

The poverty was bad enough without all the chaos of moving back and forth between tenement slums and mansions owned by family and friends where often the girls were employed as servants. Mrs. Alcott despised the attitude of her relatives calling it “the cold neglect, the crude inferences, the silent reproach of those who profess to love us and desire to help us.”6

WRITING AS AN ESCAPE FROM “WHAT IS” INTO “WHAT COULD BE”

Supported by her mother who empathized with her daughter’s needs, Louisa turned to her writing to escape her difficult world. It is not surprising that stories like “Aunt Nellie’s Diary” and her first full-length novel, The Inheritance, written around the same time, presented such fantasized versions of what life could be.

In “Aunt Nellie’s Diary,” Louisa described the poverty of one Mrs. Arnold in a romanticized fashion: “Poverty loses its bitterness when shared with those we love, and joy is doubly sweet when they partake of it with us” Unlike the Alcotts, Mrs. Arnold received help free of reproaches and judgments: “My health was going and my little ones would have soon been fatherless and motherless but for a noble warm-hearted friend whom God indeed sent to help us. With gentle, cheering words he comforted me, found this lovely home for us, gathered comforts about us and would never cease till we were all together.”7

Daniel Shealy is also struck by the contrast. “That’s true for many of her early tales,” he says. “I do think Alcott’s imagination allowed her to escape the family’s hard times, perhaps their hardest. She seems to concoct a world of her own, one where problems will eventually work out in the end.” He believes that the diary format for “Aunt Nellie’s Diary,” a technique she did not employ in other stories, made it easier for Louisa to “free her mind and write as if she were composing her own diary.” He adds, “What’s more important, the diary format allows one to present readers with interior thoughts more easily — even if it’s told from a third-person limited point of view. At the same time, it keeps a bit of sympathy for the narrator.”8

WHY DID ALCOTT ABANDON HER WORK AT SUCH A CRUCIAL MOMENT IN THE STORY?

It is possible however that the diary format compelled her to abandon the story. Biographer Harriet Reisen, author of Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women speculates: “I suspect she saw its central problem: her choice of the form of a diary by a forty-year-old woman who is of little interest either as a character or an actor in the plot. The limited point of view and strict chronology didn’t allow the author to fill in the backstories and subtle interactions that would keep the story moving and driving to a satisfying conclusion.”9

In his editorial, Andrew Gulli expressed his disappointment at the story being unfinished. “Unfortunately, after 9,000 words, the narrative was abandoned, leaving many questions unanswered.” He then came up with an ingenious idea: “We’re now looking for authors who think they are up for the task of completing it. More details will follow on our website regarding guidelines, word count, and deadline.”

In his editorial, Andrew Gulli expressed his disappointment at the story being unfinished. “Unfortunately, after 9,000 words, the narrative was abandoned, leaving many questions unanswered.” He then came up with an ingenious idea: “We’re now looking for authors who think they are up for the task of completing it. More details will follow on our website regarding guidelines, word count, and deadline.”

Jan Turnquist believes that the sharp contrast between the two girls and their interest in Edward lays the groundwork for the mystery. “When the girls meet Edward, Isabel flirts, but true-hearted Annie fascinates and Louisa even uses her knowledge of Plato (one of her father’s heroes) to show Edward’s state of mind: “Edward … recalled Plato’s words ‘If there were no pure hearts there would be no flowers'”

In this story, even as Louisa leads us into a mystery, we see clearly that “Isabel was much admired … but … Annie was more so.” Louisa makes it clear that Annie is “so unlike those around her, their affectation and desire to dazzle contrasted strongly with her (Annie’s) perfect simplicity and forgetfulness of self …” This set up leads to the cliff-hanging mystery of what Isabel did in the past. Annie is about to reveal this secret to Aunt Nellie when Louisa’s tale trails off in the perfect spot for the story contest to begin.10

What then is the dark secret that Annie was going to reveal to her Aunt Nellie? Why was Isabel so upset at the sudden appearance of Mr. Ainslie? Would this story have turned into one of Louisa’s famous potboilers? You, dear writer, can decide.

Visit The Strand website to learn more about this long-lost Alcott work and get your own copy!

1 The Strand, introduction to “Aunt Nellie’s Diary” by Louisa May Alcott, June 2020

2 Email from Jan Turnquist, June 29, 2020

3 The Strand, introduction to “Aunt Nellie’s Diary” by Louisa May Alcott, June 2020

4 Email from John Matteson, June 27, 2020

5 Harriet Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women (Henry Holt and Company, 2009), pg. 107

6 Ibid, pg. 109

7 The Strand “Aunt Nellie’s Diary” by Louisa May Alcott, June 2020, pg. 18

8 Email from Daniel Shealy, June 27, 2020

9 Email from Harriet Reisen, June 29, 2020

10 Email from Jan Turnquist, June 29, 2020