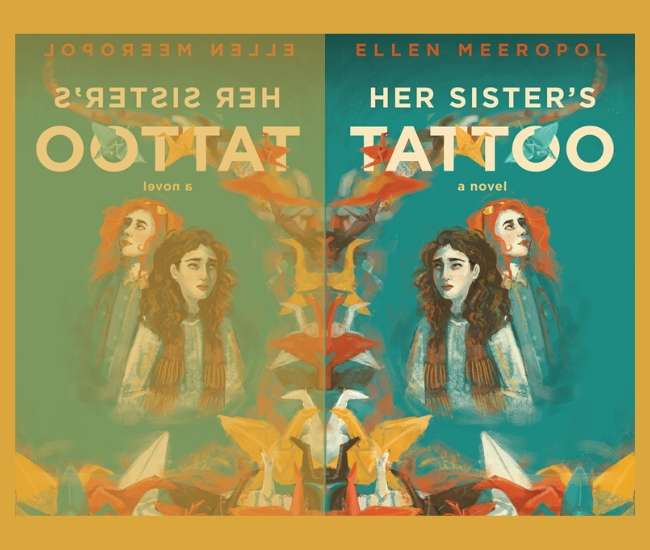

This is a powerful story of political activism, family betrayal, allegiance and love. When two sisters get arrested during a Vietnam War protest in 1968, they must decide where their loyalties lie. In Her Sister’s Tattoo (Red Hen Press) by Ellen Meeropol, politics and family are important for both Rosa and Esther, but they each must stand up for their personal priority; their futures depend on it.

When police violence took over at a protest, the politically active sisters, Rosa and Esther, take matters into their own hands and participate in a violent act of retaliation against a policeman. It is caught on camera and they are arrested and caught up in the legal system. Rosa feels she has an opportunity to fight in court for what is right and just. Esther has a baby and cannot risk jail time being separated from her daughter, so she is faced with the painful decision of whether or not to testify against her sister. Opposing points of view split the sisters apart. Their family is shattered and the two women must move on to live their lives separately.

Through alternately narrated chapters and unsent letters, we follow the sisters witnessing the outcome of their choices — the heartbreak and grief over the loss of their tight relationship and the repercussions of their actions on the day of the protest, their disagreement in court and the differences in their loyalties. Hoping for a reconciliation, we see a gradual birth of understanding and compassion over time as the sisters’ empathy and forgiveness slowly surface.

With Her Sister’s Tattoo, Ellen Meeropol reminds us that although political protests can have an element of violence, it is not a new form of expressing views — it is very powerful, it can lead to a better understanding and it can insight change. This gem of a book about political activism, betrayal, family and forgiveness is incredibly appropriate for today. It is a quick read perfect for book club discussions.

Q & A with Ellen Meeropol

Q: What inspired you to write about political activism in the late 1960s?

A: Actually, the first chapter I wrote was about 12-year-olds Molly and Emma meeting at camp in 1980 and discovering that their mothers were estranged sisters. I thought it was going to be a short story, but then I wanted to add their mothers’ stories, and I just kept going. Still, I think I always knew I would write something about the late 1960’s and the activism of those days. Like Esther and Rosa, I lived those times and some of those experiences were similar to my own. I think the questions raised by Her Sister’s Tattoo are critically relevant today: How do we balance our personal loyalties and responsibilities with the huge need to make changes in our world?

Q: The sisters have slightly different priorities when they are arrested. Esther accepts a plea bargain and in doing so throws her sister under the bus. When writing, did you explore Esther siding with Rosa?

A: Actually, I think the sisters’ priorities are more than slightly different, although their political beliefs are very similar. From Esther’s point of view, she simply told the truth about what happened at the demonstration. And, she did what she had to in order to take care of her child. So, no. I couldn’t imagine Esther going to prison with Rosa, not if it meant leaving her baby.

Q: Betrayal is a common emotion for almost all the characters in the story. Why do you think this resonates with readers?

A: I think issues of loyalty and betrayal are pretty basic emotions for many of us. We expect our family to stand with us, even when we disagree, even when standing with us might require lying. I’m interested in how we balance our ethics with family love and expectation of support.

Q: Do you think the political activism that occurred to protest the Vietnam War affected change?

A: Absolutely! I think the massive antiwar demonstrations of the late 1960’s contributed significantly to the end of the war. Of course, the North Vietnamese also played a big role in that victory.

Q: Do you think our country today breeds more or less activists than in the past?

A: That’s such an interesting question and it’s hard to answer. I think the draft was hugely instrumental in bringing many young people, men and women, into antiwar activism. Many of them were not particularly ideological in their opposition and activism, but they knew they didn’t want to fight, and maybe die, in that war. Today, there are huge numbers of young people dedicated to activism around issues like the climate crisis and violence against people of color. But these movements are so poorly covered by the mainstream media, and many people don’t know about the activism happening at a grassroots level.

Q: The sisters have a deep connection and they both find it painful to be estranged, yet they allow so much time to pass before any attempt at reconciliation. How did you decide when the time was right?

A: I wrote different reconciliation scenarios, but they felt forced. The estrangement of the sisters was deeply hurtful to both of them, so forgiveness was not a simple thing. Ultimately, the ending had to evolve from the sisters’ experiences apart, and the external events of their lives.

Q: Do you think the emotional turmoil due to the secrets and the pain that was internalized by both Rosa and Esther had an impact on their health?

A: I hadn’t thought about that, but it could be understood that way. Without giving away important plot details, both sisters develop chronic conditions and stress could contribute to those situations.

Q: I loved the way you included the sisters’ letters to each other within the story. What gave you the idea to do this?

A: I used the device of letters in a previous novel, On Hurricane Island, and found it a very useful way to show a character’s interiority. Many of us will write in a letter, or a journal (and un-mailed letters are very similar to a journal), emotions we would not speak aloud. Getting inside a character’s head and heart is critical to storytelling, and letters are one way of making that happen.

Q: What is your connection to Origami (if any) and why did you choose to give it a part in the story?

A: I’ve always enjoyed origami, especially peace cranes and Sadako’s story, and they seemed perfect for this novel. I particularly love stories that incorporate visual images as a thread throughout the book.

Q: What is your writing process? Did you know the ending right from the start? Did you create an outline or develop the characters before you wrote the story?

A: I follow the Kurt Vonnegut method. He once said that writing a novel is like jumping off a cliff and developing wings on the way down. That’s what it feels like to me. I don’t use an outline and I never know the ending. I start with a spark of some sort — a character, an image, a situation, a what-if. And then I write. It sometimes means throwing away big chunks of the beginning of a manuscript because it can take a while to figure out where the juice is in a story, but it works for me. I love being surprised by my characters and their shenanigans!

Q: What have you been reading that you recommend?

A: The last two books I’ve read and adored are The Gringa by Andrew Altschul and Glorious Boy by Aimee Liu. Authors I love and reread include Kamila Shamsie (Burnt Shadows, Home Fire) and Richard Powers (The Overstory, The Time of our Singing)

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2large9815-small-368×550.jpg

About Ellen Meeropol:

Ellen Meeropol is the author of four novels, including Kinship of Clover, House Arrest, On Hurricane Island. A former pediatric nurse practitioner, Ellen began seriously writing fiction in her fifties. She holds an MFA from the Stonecoast program at the University of Southern Maine. Her stories and essays have appeared in Guernica, Bridges, Portland Magazine, Lilith, Writers Chronicle, The Writer and Necessary Fiction.

Drawing material from her twin passions of medicine and social justice activism, Ellen’s fiction explores characters at the intersection of political turmoil, ethical dilemmas, and family life.