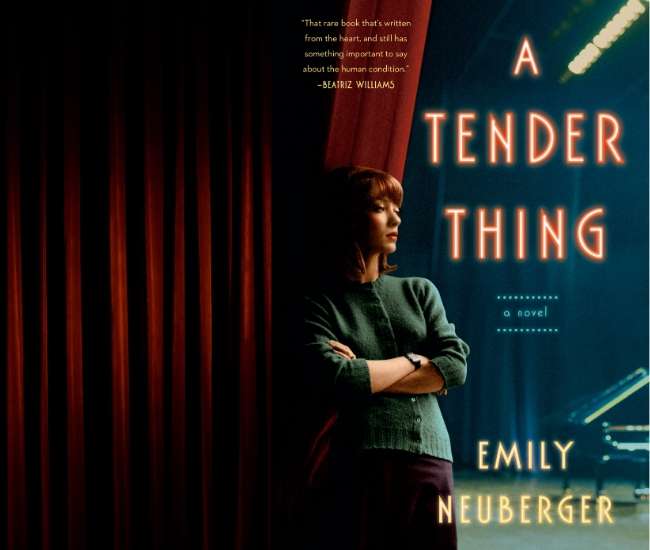

An exhilarating debut novel set under the dazzling lights of late 1950s Broadway, where a controversial new musical pushes the boundaries of love, legacy and art.

Growing up in rural Wisconsin, Eleanor O’Hanlon always felt different. In love with musical theater from a young age, she memorized every show album she could get her hands on. So when she discovers an open call for one of her favorite productions, she leaves behind everything she knows to run off to New York City and audition. Raw and untrained, she catches the eye of famed composer Don Mannheim, who catapults her into the leading role of his new work, “A Tender Thing,” a provocative love story between a white woman and black man, one never before seen on a Broadway stage.

As word of the production gets out, an outpouring of protest whips into a fury. Between the intensity of rehearsals, her growing friendship with her co-star Charles, and her increasingly muddled creative —and personal —relationship with Don, Eleanor begins to question her own naïve beliefs about the world. When explosive secrets threaten to shatter the delicate balance of the company, and the possibility of the show itself, Eleanor must face a new reality and ultimately decide what it is she truly wants.

Pulsing with the vitality and drive of 1950s New York, Emily Neuberger’s enthralling debut, A Tender Thing (Putnam), immerses readers right into the heart of Broadway’s Golden Age, a time in which the music soared and the world was on the brink of change.

Q&A WITH EMILY NEUBERGER

Q: You spent years performing in musical theatre, your first love, before entering the book publishing world and ultimately pursuing your MFA in Fiction. What triggered the shift from theatre to writing and publishing?

A: It was both a long process and an epiphany. I have always been a writer and a reader, and became obsessed with musical theatre and singing when I was very small. Like Eleanor, I loved how the music enhanced the story. In the “Edelweiss” reprise, when von Trapp is singing by himself, saying goodbye to his country, and then his family comes in, assuring him of their support, that they’ll never forget Austria … chills!

Just after my freshman year of college, I was cast in a summer-stock theatre, working on several shows in the Catskills with a group of actors. Being a musical-theatre actor is incredibly grueling. I loved some elements of the work but others went well against my personality. I didn’t want to rehearse the dance number again; I wanted to do a character study. Also, I’m not a good dancer. I always envied dancers. I was miserable. It was difficult for me to be so judged on appearance. I had some trouble with eating. It broke my heart, because I didn’t love musicals any less. I didn’t feel I had the personality for the business. It was so hard.

But I was reading a lot of books that summer, and it dawned on my one evening, that I had something else I loved, and had always loved. It was sort of like that moment in the rom-com when she realizes she’s in love with her best friend.

Writing is also incredibly unstable, but the kind of grind it requires is enjoyable to me, and even the hardest parts are rewarding. I can spend hours reading and going over word rhythm. It’s okay for it to be a slower process, too, because I can work on it a little every day, on my own. I like making up the stories. Being a writer allows me to live in the world of the fabric of the story and the character, the construction of a dream that is storytelling.

In a lot of ways, I think A Tender Thing is me processing my first love, musical theatre, and our “breakup.”

Q: What inspired the mid-twentieth-century Broadway setting of A Tender Thing?

A: I love those musicals! I think that, because of how sanitized the musical-theatre films are from the period, people believe they were just fluffy skirts and closed-mouth kisses. They weren’t! The original librettos often reckoned with themes that we are discussing today.

I was fascinated in the boom of art post-World War II, before the civil rights moment, when the world was reckoning with the horrors that humans were capable of. And then, the fifties had this neo-conservatism about sex, gender, race — putting people back into the boxes they’d sprung out of. Growing up Catholic, I’m very attracted to ideas about shame and performance of propriety. Performance in general. In time, incredible work was being created. The musicals of the ’40s and ’50s shaped the art form of today. I love how the manicured, entertaining musical numbers allow the audience to witness some difficult themes easier than in, say, a drama or a novel. A beautiful melody can smooth a tough message. I think in the time of Rodgers and Hammerstein, this was especially important, because there were things people just would not talk about. But Hammerstein, he wanted to talk about them. So he found a way. My character Don Mannheim is the same kind of writer.

Q: What kind of research did you need to do to capture the period?

A: Ask any theatre-obsessed kid, and they can probably recite the lyrics to twenty-five cast albums. That was me — I read every libretto I could find, the biographies of composers, books about how musicals were made. There’s a lot of history in those. The industry was different during the rehearsal years of RENT and West Side Story, Oklahoma!, etc. West Side Story was drafted as East Side Story, a love story between a Catholic and a Jewish Holocaust survivor, before New York City current events shifted their focus to white teenagers and Puerto Rican immigrants. Just learning these things made me ask why they were the way they were. There’s a lot to learn about history just by studying how productions got made. The money came from different places, the audiences looked different, the shows adjusted.

And I studied the songs. At NYU, I took years of repertoire classes, where we had to research the composers and present songs. We moved through the canon of musical theatre, from Gilbert and Sullivan to Lin Manuel Miranda. The information about singing comes from experience. A huge amount of the research comes straight from the musical theatre world. I definitely started with what was happening on Broadway, and moved out from there.

As for more specific research, I read newspaper articles from the time, and articles from Vogue to get fashion patterns and vocabulary. I looked at old maps and advertisements in the Subways and magazines. I also interviewed my grandparents and their peers; some of their stories are repurposed in the book. And I read, a lot. Fiction from the period and nonfiction.

Q: Women had opportunities to perform on stage during Broadway’s Golden Age, but very few worked as writers, directors, producers, etc. When did that begin to change? Who led the way?

A: It’s definitely still changing. I don’t think it’s fair to say anyone led the way, it’s more complicated than that. Women have been doing amazing things for a long time. Agnes de Mille’s choreography is iconic. And performers like Ethel Merman — she influenced how musicals were written, because writers wrote for her skill set. You wouldn’t call her a writer, but she’s more than an actress. She was a force. There have been so many incredible women prominent in the world of musical theatre for decades. Because of the nature of the art form, composers and choreographers were creating for women’s instruments, their skills as comedians, their movement — they were more than muses, they were literally shaping the art with their talent. Stephen Schwartz has said that Glinda is only a soprano because Kristen Chenoweth didn’t get to use her high notes enough in her career, and she asked him to add some in.

I think it’s a bit better now; you see women directing on Broadway more often. Fun Home, in 2015, was the first show written entirely by women — that’s so recent! Women have written shows before. They didn’t get to be on Broadway. That’s the producers. Waitress, in 2016, has the first all-female creative team. But Broadway writing is still very white. Even many of the shows that feature many actors of color are, behind the scenes, run by white men. There’s definitely an issue of tokenism on the creative teams — ten white men for everyone else. There is so much room for growth, but I think it’s an industry that has been brave in the past, and will continue to be.

Q: Eleanor O’Hanlon, your protagonist, is a singer who yearns to perform on NYC stages, a dream you fulfilled by singing at Carnegie Hall. What else do you share with Eleanor O’Hanlon?

A: While I didn’t have a Pat or a Don, I also had strong mentors. My voice teachers were incredibly important to me growing up. In college, my voice coach became a dear friend, and still is. They all taught me so much about expression in music, and the history of the form, and showed me the steps to living as a person in the arts.

Eleanor’s connection to the stories in musicals, the characters, the “arc” of the musical, is pretty analogous to mine. I’ve always loved musicals for how they addressed difficult themes; my favorite musicals are very transgressive, really pushing the form. I really was attracted to the emotion in musicals, how the combination of music and narrative can lift the spirit and take it along the journey with a character. Eleanor and I definitely share that love and obsession with the art; it can change form, as mine did, but it’s always there.

Q: Are any of the characters based on real-life people from the Broadway community, circa 1958?

A: No fictional characters are based on real people, though I do mention several real people briefly throughout the book. Julie Andrews comes up in chapter one.

This isn’t in the book, but the spirit of the story is alive in the book (Also, it may not be true.): Legend has it that during a rehearsal for West Side Story, Jerome Robbins was standing on the stage, screaming at the cast so loudly, and with so much anger, that no one warned him as he walked backward … and fell into the orchestra pit. I definitely thought about authoritarian directors when I wrote Harry.

Q: Twenty-one–year-old Eleanor arrives in New York City alone, with no real experience outside of her family’s farm in rural Wisconsin. What important lessons did she need to learn in order to tackle a leading role in a controversial interracial love story?

A: So much! Eleanor comes to Manhattan with very little life experience. Her mind is full of prejudicial beliefs. In order to play Molly, she has to find a way to leave all this behind. Molly and Luke, the characters in A Tender Thing the musical, are so proud to be together. They have to hide their relationship for practical reasons, but Molly wants to shout her love from the rooftops. Eleanor has to be able to understand this love. She has to be comfortable being seen in public kissing Charles, which, at first, is difficult for her. It’s not only their racial differences; she is a virgin, she’s Catholic and in A Tender Thing, Molly and Luke have premarital sex. She has to be comfortable expressing that part of herself to hundreds of people. It’s very private for her, and then you add that she’s crossing this intense social boundary. Charles feels it too, only for him, it’s a social boundary with potentially fatal consequences. They’re both very brave to do this. All that work has to have been done before performances.

Her lack of life experience does her a favor, though, in that she is able to learn when she comes to New York. She didn’t come by these beliefs through her own life experience, but instead from gossip, racist language, everyday sexism. She never fit in when she lived in Wisconsin, so she was willing to turn away from the prejudices her parents, peers, and neighbors lived by. Unlike many people, Eleanor was looking for a way to distance herself from her life there. She is willing to learn. Of course, all of those negative forces are still just as present in New York — but she has the chance to meet people who challenge these beliefs. She has the room to reinvent herself. By the end of the book, she hasn’t so much fixed these issues, as become aware that they even exist. Many of these prejudices stem from comfort — stick with people just like you, anything else is a threat. She learns that it’s OK to be uncomfortable, and that it’s the beginning of change. She learns that her discomfort, her parents’ discomfort, is not as important as someone else’s safety.

There’s a scene where she’s very upset about a song they’ve written for Molly, when Molly questions whether she’s willing to give up everything in her life in order to be with Luke. It makes her very uncomfortable, because it touches on her own doubts about what she’s doing. She wishes it were clearer cut, and it’s scary for her to admit that, maybe, a part of her preferred the more homogeneous life she had in Wisconsin. But she doesn’t want to admit it. She thinks that would make her weak — she wants, very badly, to make it in New York. But the song, in the end, makes the show better, because it’s a more complete portrait of Molly. Even as much as Molly loves Luke, it’s not an easy transition. If it were, everyone would be doing it. It takes strength to withstand the discomfort of moving away from the status quo.

Q: During an arduous rehearsal process, Eleanor and her co-star, Charles, become friends and then allies, despite their differences. Was that relationship based on any real co-stars?

A: No, but I was interested in platonic friendships between heterosexual men and women. I think that sometimes, because of all of the choreographed kissing and touching, any baseless sexual tension is cut. People either go one way or the other, and if there aren’t deeper feelings, it’s easy to be friends.

Charles and Eleanor are also in a unique position to understand each other. They’re both principals without power; they have tremendous scrutiny on them, but little protection. And while Charles is an experienced actor, he’s never been given an opportunity to really show the breadth of his talent before, in a principal role. So they have a lot to prove, and they’re both frightened. They are each other’s only ally.

Q: A powerful thread running through A Tender Thing is the idea of artistic integrity and the characters’ quest to achieve it. What have you learned about it?

A: I’m just putting one foot in front of the other right now and trying to do the best I can. All I really know is that I have to care about my work, and take it seriously, or else what is the point?

Coming from publishing, writer friends often ask if it was hard to hear how editors talked about work. But I found it a blessing, because the reader is the most important person in the publishing industry, and I got to see how many different kinds of readers there are. Sometimes in the MFA circuit it can seem like there’s a certain kind of something that’s important or “good,” but I think it’s broader than that — books can be moving or evocative in so many ways. I love reading and I think protecting and nurturing that love is probably the source of any artistic integrity that I have.

I can’t say anything definitive about something this important. But I do feel something when I’m writing truly to the character I know and when I’m not. It’s an ephemeral thread that I have to follow, and it’s so easily lost, but it is there.

Q: Throughout the novel, characters take advantage of others to further their own success, whether professional or personal. Have you had personal experience with that? Did you find any effective ways to get others to respect boundaries?

A: I think whenever people are passionate, there’s a lot of fear that they won’t be able to do what they love most in the world. When people are afraid, they don’t always act their best. I know I have made those mistakes. Part of it is learning to quiet the voices of insecurity in my own head, so I could be healthier and form healthier relationships.

But also, literature is different from performing. There’s only one role in each production; only one person can have it; and often it comes down to things completely outside your control. Books are born from a soup of our life experience, our heritage, the way our families talked, whatever spark differentiates my mind from someone else’s. I can never tell my friend’s story for her. So I definitely was able to move away from some of the more vicious manifestations of this mentality when I left musical theatre. But I also grew up, which is part of it, and went through some life experiences that changed my perspective.

Q: A Tender Thing is a love letter to the theatre community. Did you start writing the book with that goal in mind?

A: Theatre is magical. It’s ancient art, yet exists only in the moment; it’s the most human thing in the world, learning through play, empathizing to learn. In writing about theatre, I wrote a character who loves it for the magic that it is. I couldn’t have written Eleanor without the book being a love letter to theatre.

Q: Do you see any of the themes in A Tender Thing currently being played out on Broadway?

A: Have you heard of Hamilton? Just kidding.

I think these themes were alive in a furious way in the ’50s, as they are now. We’re in a time of moral crisis. But I don’t think these themes have ever gone away. I think the latest revival of Oklahoma! was fantastic. I also think it’s funny that people call it the “modern” Oklahoma!. I loved what they did with the casting, the staging, the arrangements. But the libretto is the same lyrics, the same dialogue. It’s brilliant that the direction pushed audiences to check their preconceived notions at the door and view the show afresh, because it’s the same show. Those themes have always been there. It’s always been a show about property, sexual shame and violence, and prejudice. So I think these are themes that we as a society wrestle with cyclically.

Q: What’s up next for you? Is there a second novel in the works?

A: I’m currently working on a contemporary novel, a love story set in the North Shore suburbs of Chicago, about a cardiothoracic surgery resident who, as a teenager, witnessed a violent crime he felt he could not report, and his experience as a man learning to save lives.

A Tender Thing is now available for purchase.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/EmilyNeuberger_PhotoCMichael_Kushner_2019.jpg

Photo © 2019 Michael Kushner

About Emily Neuberger:

Emily Neuberger is an MFA graduate and grant recipient at Brooklyn College’s fiction program, and previously worked as an editorial assistant at Viking Books. She has a music degree from NYU, where she studied musical theater and writing. A performer for fifteen years, she performed at Carnegie Hall in Stephen Schwartz’s birthday celebration and sang for Stephen Sondheim at the Music Institute of Chicago. She lives in Brooklyn, NY. A Tender Thing is her debut novel.