Marines, with their ritual, tradition, obedience and hierarchy, thrive in a profession that most Americans would tend to avoid.

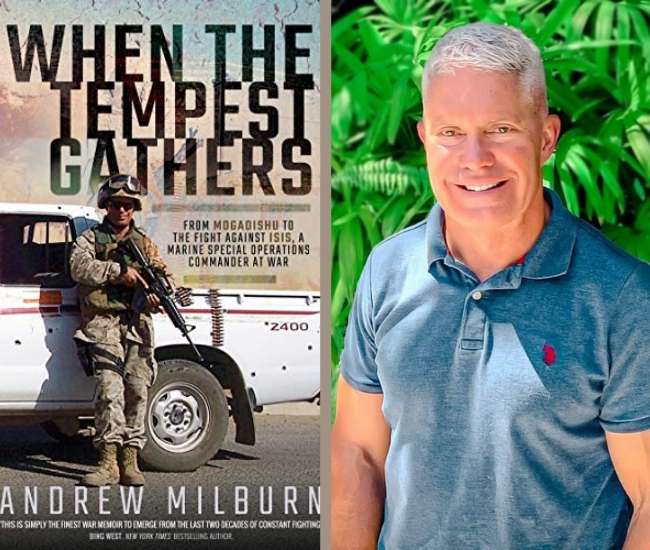

“It is the camaraderie engendered by shared hardship for a common cause that helps offset the trauma of combat, ” writes Andrew Milburn in When the Tempest Gathers (Pen and Sword Books), his detailed memoir as a Marine Corps leader in Mogadishu, Baghdad, Fallujah, Mosul and in the fight against ISIS.

Milburn has an unusual background for a U.S. Marine, and this is no ordinary war memoir. Very few personal accounts of war cover such a wide breadth of experience, or with so discerning a perspective.

The author told us more about his life as a Marine and his experience writing this book. (You can read our review here.)

Q: Why did you become a Marine?

A: I enlisted almost on a whim, driven by the desire to do something completely different from what I had experienced up to that point in life. And the final clincher was a chance encounter with three Marine security guards in the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad in early 1987.

As for what I was doing in Islamabad — it involves an unusual trip across Iran at the height of that country’s war with Iraq, when it was very much closed to Westerners. Through an improbable chain of connections, I set off by bus across Europe and Turkey to the Iranian border.

Youthful optimism is a strong antidote to the prospect of danger. During the trip, I experienced an Iraqi air raid (deep irony) while in Isfahan, was interrogated by the Revolutionary Guard in Tehran, arrested and detained overnight in Shiraz, and chased by a crowd in Zahedan, before making it across the border to Pakistan.

There my troubles weren’t over. I arrived in Quetta during mass rioting against the Pakistani authorities whose reaction was to shoot scores of people in the street before imposing a curfew. When it ended a few days later, I traveled by train to Islamabad, an interminable journey interrupted at frequent intervals by Pakistani soldiers on the search for troublesome Baluchis.

It was at the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad, where I had gone to retrieve my passport, that I found myself sharing a table with three Marine security guards. Cropped haired, fit-looking and boisterous, they regaled me with stories of travel and adventure. Later I attended a party at their residence, which they referred to as the Marine House, a plush three-story building with bar, gym and swimming pool. This is the life, I thought. Why not take a four-year sabbatical to see the world before settling down to a career as a barrister? Ten months later, after completing law school, I visited the US Marine recruiter in London (there was one then) and enlisted. I’m sure that he is still telling the story.

Q: Why did you write When the Tempest Gathers?

A: Two months prior to deploying to Iraq in 2016, I suffered a family tragedy. During the deployment I was able to stifle much of my grief by focusing on the task at hand, but upon my return it caught up with me. Faced with the full impact of my loss, I wasn’t sure which way to turn. It was a curiously helpless feeling, not one that I was accustomed to and I found myself almost desperately looking for distraction.

One evening I just started writing, not with the intention of writing a book, but rather a series of stories that my children could read when they were older to understand why I had been away for so much of their childhood. To my surprise, I found writing utterly absorbing — so much so that it helped me deal with my grief and gave me a focus outside work.

Q: What would you like readers to take away from this book?

A: This is the story of what it’s like to lead those who fight America’s war, told from one Marine’s perspective. It’s a perspective that varies widely in context, from the experiences of a raw second lieutenant leading Marines through the streets of Mogadishu, to those of a task force commander directing special operations forces in a complex fight against a formidable foe.

The story is intended to be more about the people with whom I have served than it is about me. Because I am a Marine — and without, I hope, appearing parochial — much of this story is about Marines, who in a sense belong to a world of their own. There is something enduringly familiar about their collective personality that I have always found comforting: upbeat, funny, brave, gracious, savvy and profane. And devoted to one another to an extent that often surprises outsiders.

Q: You manage to intersperse stories from the front lines of brutal combat to stories of touching and difficult personal matters. Tell us about the difficulty living in both those worlds.

A: There’s one episode in the book that captures the sharp contrast between the experience of combat and the abrupt transition back home to a totally different world. It’s a brief excerpt but sums up the sense of dislocation that many veterans of the war experienced upon returning home. I boarded a military aircraft for the first leg of the flight home, having just been involved in a firefight in which one of our Iraqi soldiers had been badly wounded:

“An hour later, sitting in the back of a Hercules C-130 heading for Kuwait, the Air Force crew chief leant down to yell in my ear. ‘Hey sir, we just got word to put down in Balad to pick up some KIA. Your call whether you want to continue on this flight. The other two guys have decided to get off and catch another one.’

‘I’ll stay.’

It was dark by the time that we touched down in Balad to collect our grim cargo: four body bags loaded aboard with reverence but none of the ceremonial trappings that would later characterize such events. Once we were airborne, the crew chief and loadmasters disappeared up front, leaving me to share the darkness with the bodies of four young Americans who, unlike me, would never see home again.”

When we landed in Kuwait, I boarded a United Airlines flight to Washington and slept the entire way, awaking only as we touched down in Dulles airport. Later that evening, unable to sleep, I walked from my apartment to a nearby bar in Old Town, Alexandria. There, surrounded by a boisterous crowd singing along with a mock-Irish band, I felt utterly alone, unreasonably resentful that life for those around me appeared so untouched by the war.

In so far as this story is a memoir, I have made every effort to describe things as they were, rather than how I may have wanted them to be. I am open about the hard lessons that I have learned and the mistakes that I have made along the way. And — although this was particularly difficult for me — I am candid in discussion my own struggles with the isolation of command, post combat trauma and family tragedy.

I like to think that even readers who are not particularly interested in the military will find some inspiration in this part of the story, which is, I think, ultimately about hope and resilience.

Q: You raise some Big Picture issues that deal with the “why” of war and the decisions by the Powers That Be to engage in wars in the first place. Tell us your thoughts on this matter.

A: During the last two decades, it has seldom been easy to discern a link between military efforts and any coherent overarching strategy. Nor, with the exception of a few brief flurries, has there been real Congressional scrutiny into the conduct of America’s wars. Of course, for such a debate to happen, there would have to be a level of public interest fueled by a sense that the American public has something at stake.

Perhaps that is what is missing. A very small percentage of Americans serve in today’s military, so it should be no surprise that they feel little personal investment in the wars currently fought on their behalf. Without that sense of investment there is nothing to drive media attention or Congressional action: “America is not at war; the Marine Corps is at war; America is at the Mall” was an oft-repeated refrain by graffiti artists from Al Qaim to Camp Fallujah. Hence, perhaps, the curiosity of my fellow passengers, who told me they didn’t know anyone in the military.

For more on Andrew Milburn, visit his BookTrib author profile page.

RELATED POSTS

“The Beekeeper” Perseverance, Bravery, Strength and Escape from ISIS

Semper Fidelis: 6 Novels Featuring Marines

This Veterans Day We’re Showcasing 12 of Our Authors Who Served the Nation

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IMG_3955-1.jpg

About Andrew Milburn:

Col. Andrew Milburn was born in Hong Kong and grew up in the United Kingdom where he attended St. Paul’s School and University College London before enlisting in the U.S. Marine Corps as a private. As a Marine infantry and special operations officer, he has commanded in combat at almost every rank. He retired in 2019 as the Chief of Staff of Special Operations Command, Central (SOCCENT), the headquarters responsible for the conduct of all U.S. special operations throughout the Middle East. He and his wife Jessica live in Tampa, FL, with their two children and a coterie of rescued dogs.