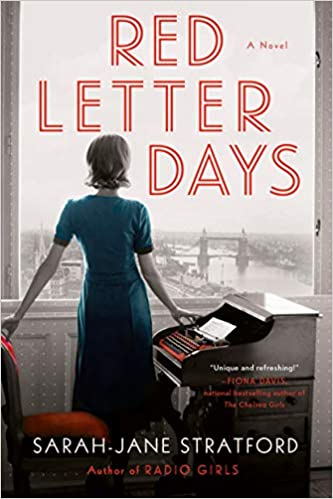

Red-Letter Days by Sarah-Jane Stratford

Red Letter Days (Berkley) by Sarah-Jane Stratford is a vivid portrayal of artistic life during the Red Scare and the challenges women screenwriters faced in the era’s entertainment industry. It is also a witty and harrowing tale of intrigue, friendship and romance.

Phoebe Adler is making her way as a female television writer in 1955 when she finds herself subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Phoebe’s saucy and loving sister is deathly ill, and she laments having to leave her behind. However, unable to work in America and betrayed by neighbors and friends who instantaneously ostracize her, Phoebe books passage on a ship bound for London, where a tight-knit group of blacklisted refugees has been gathering. Upon settling in, resourceful Phoebe tracks down Hannah Wolfson, a fellow expat and television producer sympathetic to her plight. Together the women launch a kids’ show based on Robin Hood, with cheeky storylines that provide an implicit criticism of the hysteria back in the States. Phoebe soon proves herself, and she and Hannah form a tight bond.

Stratford imbues the text with lively energy and a wry voice as she illuminates the sexism that both of her main protagonists face. For example, in reference to disposable female television characters, the narrator says, “… the censors preferred it when a bad girl [on a show] was killed if there wasn’t time to reform before the commercials ran.” A nimble stylist, Stratford’s (sneakily feminist) dialogue suits her quick-witted and hard-boiled broads, as if lifted from classic films like His Girl Friday. For instance, when confronting a man who asks Phoebe if he should call her a cab, she replies, “I’ve been called worse.”

In spite of its constant and quickly escalating dangers — tapped phones and shady men lurking in trench coats — Phoebe’s new life abroad has its bright spots, including a growing romance. Upon meeting her beau, the narrator says, “He had a mole on his cheek and could fence with that nose. A detail Phoebe found rather appealing.” FBI investigators and meddling reporters scrutinize the show, whose writers are all working under assumed names, and Phoebe is all but certain to be nabbed. She and Hannah face an ultimate test to their joint resourcefulness.

Stratford displays an impressive ability for illuminating the 1950s in both its grit and its charm. Nostalgic for the New York she’s left behind, Phoebe thinks of “her favorite Midtown diner, flossy, bright loud. A fat red stool and a white-capped counterman asking her in a good-natured holler, ‘What’ll it be, honey?’” She also ably portrays the dark days of surveillance and paranoia. Careers and friendships crumbled during the thirteen agonizing years of Red Madness, ensnaring any number of innocents, including anyone who vocally “touted the virtues of the New Deal” or joined a union, which accounts for the legions of Hollywood writers who found themselves exiled. However, Phoebe and Hannah’s story is no time capsule. As Stratford writers in her Author’s Note, “It is staggering to think of the United States, emerging victorious and a superpower at the end of World War II, should have been so afraid of the spread of Communism that it would start persecuting its own citizens.” Indeed, similar to the Robin Hood show with its social critique wrapped in a palatable form, Red Letter Days is a timeless and relevant story about the dangers of bias, conformity and groupthink.