When my first novel, Water on the Moon (She Writes Press), came out, I was invariably asked about the subplot of teen lesbianism. In my new novel, Tilda’s Promise, I have included 14-year-old Tilly who is questioning her gender. And I will no doubt be asked why I chose to include that particular uncertainty.

Want more BookTrib? Sign up NOW for news and giveaways!

When it comes to the acronym, LGBTQ, I lean heavily on the Q (often used to signify “questioning”). And when it comes to transgender youth, I do it for reasons that have nothing to do with whether I’m “for it” or “against it.” I’m certain no parent with a child or adolescent questioning his or her gender ever said, “Wonderful! We always wanted a son/daughter instead of you!” The truth remains, however, that how a parent responds to a questioning child has everything to do with his or her potential for a happy future.

My own experience with transgender youths began years ago with Catherine, my goddaughter, and daughter of a dear friend. Because her husband was overseas on a long-term business contract, I became a parent surrogate, attending prenatal classes with her, long before Catherine would become Catherine.

I was a sounding board in the years when Catherine and her parents faced each new challenge, from questioning to transition. Not every teen uncertain about his or her gender goes on to transition or to undergo gender-confirming surgery, but Catherine did, in Canada, several years ago. And I was there for what she saw as her real birth. The surgery was successful but not without complications once she returned home. Catherine and her mother traveled the country before finding proper care.

Fortunately, from the beginning, Catherine’s parents did the most important thing they could do: they listened. They were in shock and denial. They were angry, hurt, and shaken to the core, but they listened. They educated themselves and saw to it that Catherine received competent counseling. Overcoming their own initial fear and misgivings, they knew they faced a choice: support Catherine on her journey or lose her. They chose to be supportive.

As a questioning and then trans teen, Catherine was among a population often disowned and sometimes forced to leave home. She was among a group who are ostracized by peers and teachers at school, who are discriminated against, often teased or bullied or who become victims of violence, all of which leaves a profound mark.

I have to admit that I was more than skeptical when I first learned of Catherine’s questioning. In fact, I could not accept it. But why? I finally had to confront my own hostility toward her “coming out.” I simply could not walk in her shoes as she changed from high tops to heels. And to be honest, it wasn’t until I saw her on that gurney in Canada that I realized what she was willing to endure to be who she knew she was.

That’s what it took for me to open my mind and my heart. I had to admit that I had been unable to truly put myself in Catherine’s place. Now I write about questioning kids.

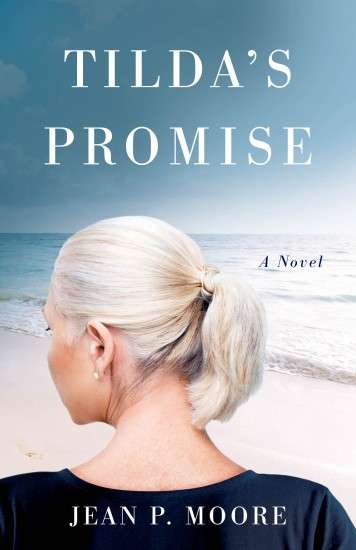

When I created the character of Tilly, I carried with me all that I had learned from Catherine. I knew I would have to show the uncertainty that would lie ahead for her.

I began by showing the effect of Tilly’s new gender doubts on those who loved her most: her mother and father and her grandmother, Tilda, the main character. Each began in denial. After all, Tilly was perfect, a good student, a talented dancer, and so each had a rationale for not seeing what was in plain view: Tilly’s questioning. Her grandmother finally recognizes that she was too consumed with grief after the death of her husband to acknowledge the signals Tilly was sending.

To fully render Tilly’s questioning, I entered into her consciousness through a shift in point of view, to show her isolation, confusion, and doubt—yes—but also her perseverance and strength. I also used her sessions with her psychotherapist, Dr. M., as a way to penetrate more deeply her coming to terms with her gender identity.

Ultimately, I would send both grandmother and granddaughter on a journey to the land of the discoverers, to Portugal, where there would be no easy answers but many discoveries of their own.

When I write about questioning and transgender teens—and their parents—I create the fictive world they would face in reality. For support, when I delve into the research, I rely on medical evidence.

In a recently published survey in the journal, Pediatrics, researchers revealed startling findings, the most significant of which is “the high frequency of mental health conditions” among transgender youth. According to the study, especially problematic “are the results for suicidal ideation and self-inflicted injuries.” The study concludes that these children and adolescents need not only “evaluation of mental health needs but also urgent implementation of social and educational measures of gender identity support.”

Tracy A. Becerra-Culqui, co-author of the study, when asked in Medical News Today (April 2018) about the results, said she hoped the research would create “awareness about the pressure young people questioning their gender identity may feel, and how this may affect their mental well-being.” She went on to note how crucial it is for young people who are questioning their gender identity to get the necessary social and educational support they may need.

May the Catherines—and the Tillys—of the world always find that support. And may I help by telling their stories.

Tilda’s Promise is now available to purchase.