The Real Lolita by Sarah Weinman

This story appears through BookTrib’s partnership with the International Thriller Writers. It first appeared in The Big Thrill.

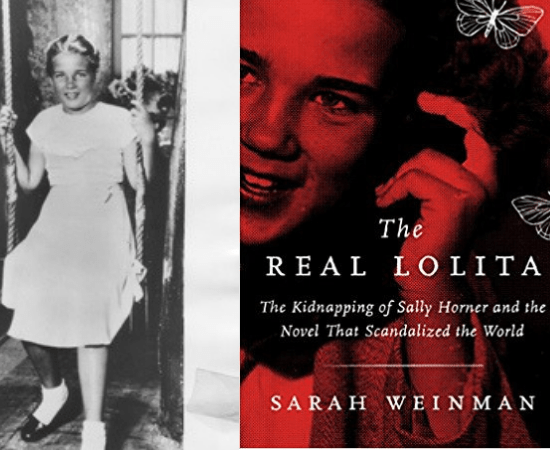

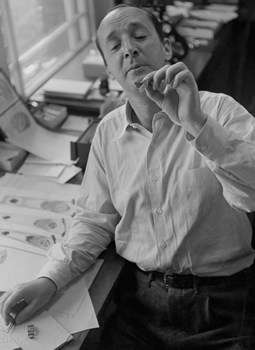

When discussing a novel, many an author will be only too happy to cite the real person who inspires a character or the news story that sparks the idea for a plotline. But Vladimir Nabokov, no great surprise, wasn’t like other authors. He always denied that the case of Sally Horner, abducted at the age of 11 from Camden, New Jersey, in 1948, inspired his 1955 novel Lolita. Sarah Weinman argues otherwise, in her meticulously researched and movingly written nonfiction book The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandelized the World (Ecco).

In so doing, Weinman became a literary detective, poring through newspaper accounts, visiting courthouses and other sources of documents, and interviewing remaining relatives of those whose lives were forever changed by the Sally Horner abduction. Yet as fascinating—and as troubling—as that crime was, it’s only one part of the book. Weinman also examines Nabokov’s creative processes, finding the parallels to Lolita and probable timeline of influence.

“Lolita is an outstanding work of art and its genesis has incredibly complicated roots, and Nabokov himself is an incredibly complicated man,” Weinman says.

The book’s narratives unfold on parallel tracks: One is the true story of Sally Horner, the 11-year-old daughter of a struggling single mother who was coaxed to go on an Atlantic City “family vacation” by a 50-year-old ex-con named Frank LaSalle, who then disappeared for almost two years on a cross-country horror of rape while hiding from the law. The second is the career of Russian emigree Nabokov, who in 1948 had finished teaching at Wellesley College and was starting at Cornell, and was just beginning the “stop and start” of writing the novel that became Lolita.

The national newspaper stories covering Sally’s rescue in 1950, and the headlines in 1952 when she died in an unrelated car accident, correspond to the period when Nabokov, by his own admission to friends, was struggling with writing the novel. He completed the manuscript at the end of 1953.

What did Nabokov know and when did he know it “is pretty much the phrase I had in mind while I wrote about this,” Weinman says.

A journalist and editor of two anthologies on women crime writers, Weinman tracked down Sally’s relatives and friends, the daughter of the woman who finally persuaded Sally to call her mother, and even the child of Frank LaSalle, who died in prison. LaSalle had enrolled Sally in a series of schools and put on an act of being her father to neighbors and her classmates.

After all of the research that Weinman conducted, first for a story in Hazlitt and then as the book for Ecco, is she convinced that Nabokov based 12-year-old Dolores Haze on Sally Horner? “I think it is pretty likely, because of how much detail he put in that corresponds to what happened to Sally,” Weinman says.

When later questioned by a couple of curious journalists, Nabokov said there was no connection between Horner’s life and Lolita. What complicates this is that he does explicitly mention the case in his novel. Near the end of the book, Humbert Humbert muses, “Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank LaSalle, a 50-year-old mechanic, had done to Sally Horner in 1948?

Yet the author also maintained in interviews that she was not an influence on his creation of the story. Weinman says, “Well, that was part of his philosophy. He believed that it was not artistically viable to appropriate someone’s real story.” In The Real Lolita, Weinman includes a letter in which Nabokov’s wife, Vera, firmly denies any connection between the novel and Sally Horner in answer to an inquiry.

Beyond the question of the Sally Horner experience, Nabokov “did not just conjure up Lolita out of thin air,” Weinman says. “This was the product of about 20 years’ worth of exorcising this particular compulsive demon that he had. It was an unscratchable itch. He started off with a poem, and then he wrote The Enchanter that didn’t get published in his lifetime, and then he finally writes Lolita, and even after Lolita, he’s still on it. Look at Ada or Ardor, at Transparent Things, and he’s still exploring this particular illicit idea. It’s a continuum.”Other interesting aspects of her book are the journey to publication for Lolita in a time of censorship, and Nabokov’s own preoccupation in his literary output with the sexuality of prepubescent girls.

In Lolita, Humbert Humbert is obviously the protagonist, and all perception and understanding of the child Lolita and how she felt is filtered through him. “Looking at Lolita and looking at all the unreliable narrators who have populated literature since, I think it still has the capacity to shock,” Weinman says. “Nabokov is really trying to get under the reader’s skin and do a sleight of hand and a lot of manipulation. It really is seduction by reader.”

But undeniably the novel is glossing over a series of rapes. Dolores Haze has no voice in the matter we can trust as hers. Trying to do justice to Sally Horner, her intelligence and kindness, and resilience through her horrific experience, was one of Weinman’s goals in the book. Sally made friends who valued her; she left behind bereaved family when she was killed in a car accident at the age of 15.

That was what led Weinman to the “shoe leather” part of her research for the book: traveling to Camden and Trenton for documents and “my favorite thing ever, going to archives.”

Seeing the places where Sally lived was important to Weinman. “Last week, I was in Atlantic City and I was just walking the boardwalk. Finding the address where Frank lived and then took Sally…it floored me. I wasn’t expecting to find it, and to see it preserved the way it is, I felt this incredible rush of connection.”

In The Real Lolita Sally Horner has found her place at last.

The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandelized the World is now available to purchase.

Buy this Book!

Amazon