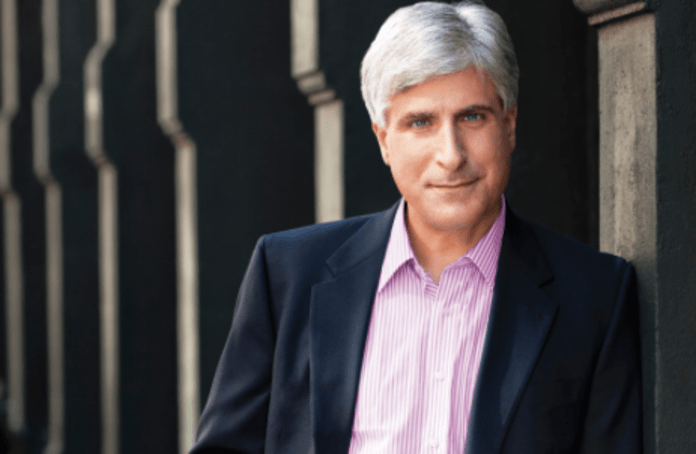

Steve Berry calls himself the poster boy for persistence. He refused to give up—although he thought about it a few times. But his persistence resulted in worldwide fame and an annual trip to The New York Times bestseller list. He has written stand-alone thrillers as well as his famous “Cotton Malone” series.

Steve Berry was a successful small town lawyer in the 1980s, dealing with the typical array of cases for a litigator—everything from murder and rape to evictions and personal injury—not to mention the everyday stuff like drafting wills and real estate closings. For at least a decade he had a nagging feeling he couldn’t shake. A voice in his head kept telling him he needed to write. This was during the time when fellow southerner and lawyer, John Grisham, rose to the top in what was becoming the increasingly popular legal thriller genre. Steve thought he could write one, too, and set out in 1990 to do just that.

“But I did something horrible,” he says. “I wrote what I knew. I wrote a legal thriller with 170,000 words, which will tell you how bad it was right off the bat. But it’s the best thing I will ever write.” Today, that manuscript sits atop his writing desk as a daily reminder of his perseverance and will to succeed.

“What do you do when you finish writing a horrible manuscript?” he asks. “You write another one.” And Steve did. They were equally horrible, he admits. But they were necessary to learn his craft.

“Ninety percent of writers never finish what they start. But I did. It was awful. But it was complete. And completing a manuscript is just the first step in the long journey of a writer who wants to eventually get published. You read. You write. You rewrite. And you write some more. I didn’t go in with rose-colored glasses.”

Perhaps it was seeing the turmoil his clients faced in court, where verdicts were not always fair nor just, that gave him a more realistic perspective on what it took to succeed as a writer. His first three manuscripts taught him writing was hard and there was a craft he needed to master. “There actually are right and wrong ways to do this.”

So he found a writers group in Jacksonville, Florida, an hour’s drive south of his Georgia home, and every Wednesday evening for the next six years he met with fellow writers and dug into his craft. “Seventy percent of what you hear in a writer’s group is garbage,” he points out. “The rest is gold. How do you know the difference? Time teaches you.”

From 1990 to 2002 he wrote eight manuscripts. He gave up on the legal thriller idea and switched to his passion: international suspense thrillers, a combination of action, history, secrets and conspiracies. Steve is a rabid a history buff, so he began hitting the books in the evening researching plot ideas. Like an attorney preparing for trial, he would search for little known historical facts that would support a full manuscript. And he learned a valuable lesson during this time.

Never write what you know.

Instead, he says, “Write what you love.”

He was doing all of this while still running his law practice. He was also an elected county commissioner with a constituency of 10,000. So every morning he would arrive at his office between six thirty and seven and write until nine, when he would then turn his attention to handling cases and making a living. Occasionally, if he had free time at lunch, he would sneak in an hour or so of writing. But the vast majority of his work was done during those early mornings.

“No one ever actually saw me write a word. I was always there alone.”

His first three novels, he admits, “were horrible.” But, “four through eight were somewhat better. Maybe only bad.” Eventually, his fourth written novel, The Amber Room, became his first published novel, but not until 2003.

His first three novels, he admits, “were horrible.” But, “four through eight were somewhat better. Maybe only bad.” Eventually, his fourth written novel, The Amber Room, became his first published novel, but not until 2003.

In 1994, after four years of writing and studying his craft, he felt he had five decent manuscripts. So he set out to find an agent the way he prepared for a court case. He dove into research. Using the Guide to Literary Agents, he created a list of 400 agents who represented the thriller genre and then mailed every one a query letter. He was tenacious.

About 80 or so were polite enough to respond. Ten expressed tepid interest. But one, New Orleans agent Pam Ahearn, saw something in his query she liked—his synopsis.

“I think women write better synopses than men. But Steve’s was good,” says Ahearn.

She explained that it read like a mini-thriller. “I just felt like, with him, something would click.” Yet, the book he sent her, titled Fatal Cure, never sold. But, Ahearn says, “I could see he was capable of writing a bigger book.” She took all five of his manuscripts and began sending them to the seventeen different publishing houses that then existed. For the next seven years, she pressed his manuscripts into editors’ hands without success. In all, she mailed out manuscript after manuscript, and garnered 85 rejections.

“It cost her a lot of money to send those out,” Steve says. “And she never charged me a thing.”

One of the problems, he later came to realize, was the Cold War was over and publishers in the late 1990s had decided that spy thrillers were dead. Pam had circulated all of his manuscripts to all of the major houses and the well appeared dry. But in 2002, seven years after he wrote it, Steve pulled his manuscript for The Amber Room out of a drawer and urged her to circulate it again. Pam questioned the ethics of sending a manuscript out a second time. A double submission to a publisher just wasn’t done. But it had been seven years since the manuscript had gone to an editor.

“No one would remember it,” he told Pam.

And no one did. Fortunately, Dan Brown’s yet-to-be published novel, The Da Vinci Code, was creating a lot of buzz in publishing circles. Word was that Doubleday editor, Jason Coffman, had something special. It wasn’t exactly a spy thriller, more action, history, secrets and conspiracies. Guess what Steve had been writing? That similarity did not go unnoticed at Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, where editor Mark Tavani was on the lookout for something like Da Vinci.

So Pam submitted The Amber Room again.

Not long after, she was waiting for a connecting flight on her way home from a writers’ conference when she checked her voicemail. Tavani made her an offer. On the 86th attempt, Steve had a manuscript in the right place, at the right time, to the right editor. She immediately faxed Steve, who was vacationing in Copenhagen. He returned to his hotel after a day of touring to find the fax on the dresser in his room. Ballantine Books had picked up the rights to The Amber Room and offered him a $37,500 advance for that book and one other.

“I remember reading it and just sitting down on the bed and saying, ‘I did it. I finally did it.’ ”

“He was stunned,” says Ahearn. “The $75,000 advance for his first two books was ten times what he had ever expected.”

Steve celebrated that evening dining on North Sea lobster. The next day, while having a meal at the Café Norden, he spied from his second floor perch, a 17th century building facade on the other side of Hojbro Plads—one of Copenhagen’s busiest town squares. “And something interesting happened. Cotton Malone popped into my head.”

His future series protagonist would be a retired-Justice Department agent, living in Copenhagen, owning rare bookshop in Hojbro Plads. He would not be a superman spy or a Bond-style stud, but a working stiff with an ex-wife and child. More details flooded his mind. He thought those pieces of paper with all those first impressions had been discarded, but he found them a few years ago. They now also sit by his writing desk.

At this moment in time, Cotton Malone was not yet Cotton Malone. The name came later, at his writers group meeting, shortly after he returned to the states. His friend, Daiva Woodworth, one of the more reserved members of the group, castigated him for his protagonist’s name. Steve had nick-named him Pepper, after a local probation officer.

“I thought it was different,” he says.

But Daiva told him it didn’t sound right and suggested “Cotton.” Steve instantly fell in love with the name and Cotton Malone became his protagonist in what would soon become an extremely successful series of international thrillers. So far there have been twelve, and there are more to come.

Five months after The Da Vinci Code hit bookstores in 1993, The Amber Room was published. The popularity of Dan Brown’s book catapulted sales of The Amber Room. A blurb on the cover from Dan himself was no small matter either. He called it “my kind of thriller.” Eventually, 44,000 hardcovers were printed (which was huge for that time), and it reached The New York Times extended list at number 32. The mass market did even better. Eventually, the novel sold more than a million copies.

“I’m the poster child for ‘don’t give up,’ ” Steve says. “I stayed there long enough until my time came, and the only reason my time came was I didn’t quit.”

Ahearn agrees. “Steve has always been driven. He had the long view in mind. He wanted to make this his career and had a great deal of discipline. He was an overnight success after twelve years.”

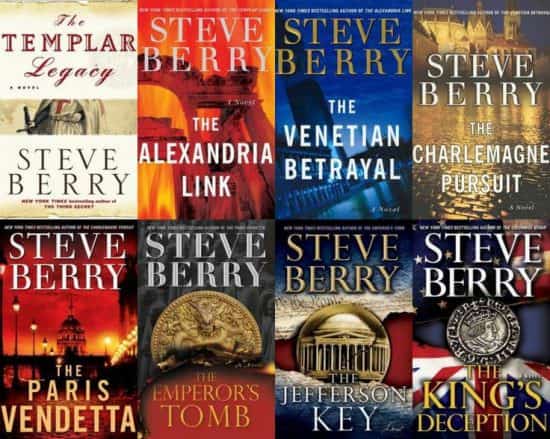

His second book, The Romanov Prophecy, sold even more copies and his next one, The Third Secret made The New York Times bestseller list. The Cotton Malone series began in 2006 with The Templar Legacy—which remains his bestselling book of all.

His second book, The Romanov Prophecy, sold even more copies and his next one, The Third Secret made The New York Times bestseller list. The Cotton Malone series began in 2006 with The Templar Legacy—which remains his bestselling book of all.

Steve began writing when he was 35 years old, and was finally published just after he turned 47. “This business is brutal, merciless, hard as hell. So one thing you can’t afford to be writing is something you don’t love.”

Steve also positioned himself to succeed. He wrote all of his rejected novels, including The Amber Room, in twelve months. Why? Because he knew if he ever made it, a publisher would demand a book every year and he needed to learn how to do just that.

Throughout his twelve-year struggle to get published, Steve worked full-time as a lawyer and also served in public office. The prospect of giving up his law practice and writing for a living scared the hell out of him. His good friend, novelist David Morrell, warned him not to give up his day job after he published his first book. He needed to wait until he was well established.

“David told me to wait until book seven, then take a good look at where you are. Then I got to the point the writing was definitely taking over. It was consuming more of my time than practicing law.”

Finally, thriller author Jim Rollins sat him down to talk about his future.

“Jim had an exercise, one he went through when deciding to stop being a veterinarian. We figured out how much I make per page on each book, then figured how many pages a day I write, then compared that to what I was making as a lawyer each day. That’s when it became clear that I made far more money writing than being a lawyer. Jim told me it was time to go full-time.”

Even so, Steve says he was terrified.

But he closed down his practice on December 31, 2008, sold his law building and moved to St. Augustine, Florida—a city filled with history—to ply his new career. As of now he has 20 million books in print in 51 countries and 40 languages around the world. Today, he can sometimes be found on the golf course in the afternoon near his home. He plays alone. And while his golf bag includes all of the prerequisite clubs, there is always a notepad tucked inside. A lot of book plotting happens on that golf course. Just like during his legal days, Steve is always working. After all, like he says, it’s a brutal business.

But brutal or not, he’s doing what he loves.

The Amber Room, Steve Berry

Start to Finish: 12 Years

I want to be a writer: Age 35

Experience: Attorney

Writing Time: 1 Year

Agents Contacted: 400

Agent Responses: 80

Agent Search: 60 days

First Submission to Publisher: 1994

Time to Sell Novel: Seven Years

First Novel Agent: Pamela Ahearn

First Novel Editor: Mark Tavani

First Novel Publisher: Ballantine Books

Inspiration: James Michener, David Morrell, Robert Ludlum, Clive Cussler

Advice to Writers: Write what you love, not what you know.

Website: www.SteveBerry.org