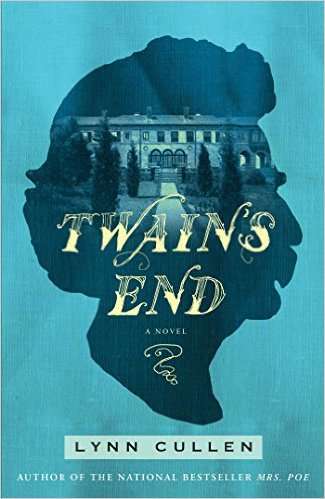

Twain's End by Lynn Cullen

In the end, “Mark Twain” himself wasn’t a real person—he was a pseudonym (and a persona) invented by Samuel Clemens and he was perhaps the greatest popular culture superstar of his time. As a novelist, essayist and public speaker, Clemens occupied a spot at the zenith of public attention.

Without the 19th- and 20th-century equivalents of TMZ and tabloid newspapers, however, we have very little evidence of what Clemens was like behind the Twain facade. But in the new novel Twain’s End (Gallery Books, 2015), author Lynn Cullen sheds new light on what might have been the complicated relationship between Clemens and his private secretary, Isabel Lyon.

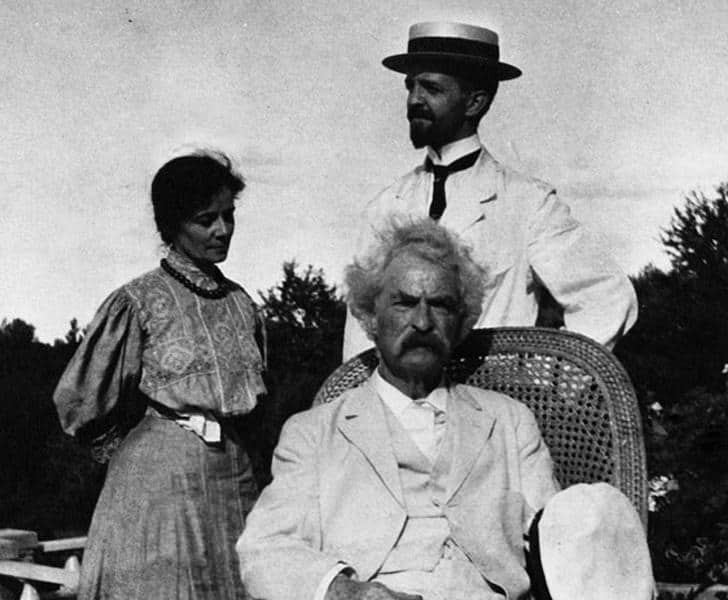

In March 1909, Twain happily gave his blessings to the marriage of Lyon and Ralph Ashcroft, Clemens’s business manager. A month later, however, he fired both and went on to eviscerate the couple in a 429-page rant in which he called Isabel “a liar, a forger, a thief, a hypocrite, a drunkard, a sneak, a humbug, a traitor, a conspirator, a filthy-minded and salacious slut pining for seduction.”

Wow, Sam, don’t hold back—tell us how you really feel.

And that wasn’t all. Clemens and his daughter Clara went on to disparage Lyon in the newspapers, effectively wiping out nearly seven years of devoted service that the former secretary had provided for the family. How exactly did she go from being the beloved assistant who ran Clemens’s life to a woman who he was so seemingly anxious to destroy? The answer to this real-life question becomes the foundation for this book of historically speculative fiction.

In the novel, the relationship between the two began when Lyon, age 25, was hired by Clemens. She falls passionately in love with her boss, and after his sickly wife Olivia dies, Lyon becomes Twain’s hostess in the author’s home. She wants to marry him, but while Clemens lusts after her, he believes that marrying her would ruin the reputation of author Mark Twain, a reputation he is eager to keep intact.

Throughout the novel, Clemens is portrayed as “a Jekyll-and-Hyde character,” in the words of Kirkus Review: “Twain, the warm and charming humorist, beloved by his fans, [and] Clemens, an egotistical, possessive, tyrannical bully, humiliating his wife, brutalizing his daughters, despised by those closest to him.”

How much of Twain’s End is fiction and how much is speculation? Cullen said that she based the novel on Lyon’s diary, Twain’s writings and letters, and events in his boyhood that left deep impressions on the man. “I don’t ever consciously divert from the facts,” Cullen said in an interview with the Huffington Post. “It’s my game with myself to compile all the details I’ve gleaned from biographies, autobiographies, period travel guides, and such; from my characters’ writings; from family photographs; from my travels to every place my characters had visited together; and, in this case, from the entries of Isabel Lyon’s diary, housed in the Mark Twain papers at University of California, Berkeley; and then see how they relate. My thrill is in finding the connections between all these bits.

How much of Twain’s End is fiction and how much is speculation? Cullen said that she based the novel on Lyon’s diary, Twain’s writings and letters, and events in his boyhood that left deep impressions on the man. “I don’t ever consciously divert from the facts,” Cullen said in an interview with the Huffington Post. “It’s my game with myself to compile all the details I’ve gleaned from biographies, autobiographies, period travel guides, and such; from my characters’ writings; from family photographs; from my travels to every place my characters had visited together; and, in this case, from the entries of Isabel Lyon’s diary, housed in the Mark Twain papers at University of California, Berkeley; and then see how they relate. My thrill is in finding the connections between all these bits.

“As a novelist, I have the freedom to use all these components to look at the bigger picture,” she said. “It’s my job as a novelist to look for the truth which can be found between the lines.”

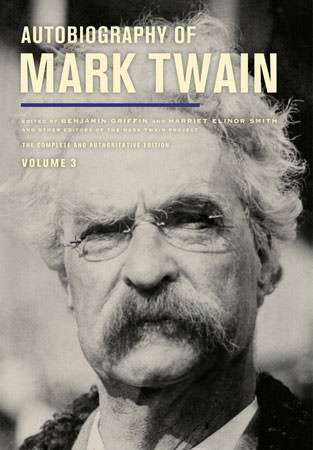

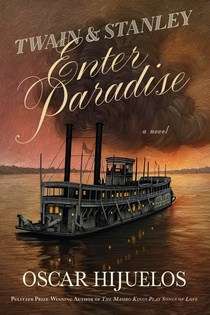

The release of Twain’s End comes at a time when the legendary author will be in the public eye once again, 105 years after his death. On October 15, Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 3 will be published by the University of California Press, followed in November by the release of Twain and Stanley Enter Paradise by Oscar Hijuelos. The latter is another work of historical fiction, this one based on the 37-year friendship between Twain and noted explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley.

The release of Twain’s End comes at a time when the legendary author will be in the public eye once again, 105 years after his death. On October 15, Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 3 will be published by the University of California Press, followed in November by the release of Twain and Stanley Enter Paradise by Oscar Hijuelos. The latter is another work of historical fiction, this one based on the 37-year friendship between Twain and noted explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley.

While we may never truly know the man history knows as Mark Twain, Cullen says her novel conveys the double-edged sword of his true nature, one that kept him separated from those who loved him most. “With the success that Clemens found after creating his Mark Twain persona came the price he had to pay for it: playing along with the act to keep the love of his adoring public,” she told the Huffington Post. “Honing the exterior of Mark Twain until it shone—allowing him to be just a little lovably naughty—was the Clemens Family enterprise.”

“As much as he loved them, Samuel Clemens was astonishingly unable to empathize with his family,” Cullen said. “His failure to do so would hamper any chance of his ever communicating with them.”

Buy this Book!

Amazon