Americans have a strange relationship with grammar. Anyone who spends a significant amount of time on Facebook, or perusing the comments section on YouTube (or any website, really, where people are allowed to comment) might conclude that as a culture, we are losing our grasp on the English language. Does anyone know the difference between your and you’re anymore, or there and their? Can anyone explain what an apostrophe is really supposed to do? Despite these difficulties, or perhaps because of them, we seem to love to talk about grammar. We even have a holiday for it: March 4, National Grammar Day.

Americans have a strange relationship with grammar. Anyone who spends a significant amount of time on Facebook, or perusing the comments section on YouTube (or any website, really, where people are allowed to comment) might conclude that as a culture, we are losing our grasp on the English language. Does anyone know the difference between your and you’re anymore, or there and their? Can anyone explain what an apostrophe is really supposed to do? Despite these difficulties, or perhaps because of them, we seem to love to talk about grammar. We even have a holiday for it: March 4, National Grammar Day.

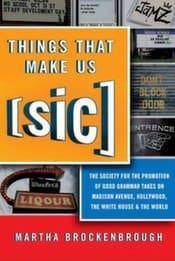

The day was established in 2008 by Martha Brockenbrough, founder of the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar, and author of Things That Make Us [Sic] (St. Martin’s Press, 2008). Brockenbrough’s book is only the tip of the iceberg. Lynne Truss’s Eats, Shoots, and Leaves (Gotham, 2004) was a #1 New York Times bestseller. Another bestselling author, Bill Bryson, tackles the language in the 2002 book Bryson’s Dictionary of Troublesome Words (Broadway), and Patricia T. O’Conner’s Woe Is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English (Riverhead 1996) is now in its third edition, and is one of five books O’Conner has written about the English language. These books—each part reference and part story—suggest a national interest in the ins and outs of our slippery language.

The day was established in 2008 by Martha Brockenbrough, founder of the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar, and author of Things That Make Us [Sic] (St. Martin’s Press, 2008). Brockenbrough’s book is only the tip of the iceberg. Lynne Truss’s Eats, Shoots, and Leaves (Gotham, 2004) was a #1 New York Times bestseller. Another bestselling author, Bill Bryson, tackles the language in the 2002 book Bryson’s Dictionary of Troublesome Words (Broadway), and Patricia T. O’Conner’s Woe Is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English (Riverhead 1996) is now in its third edition, and is one of five books O’Conner has written about the English language. These books—each part reference and part story—suggest a national interest in the ins and outs of our slippery language.

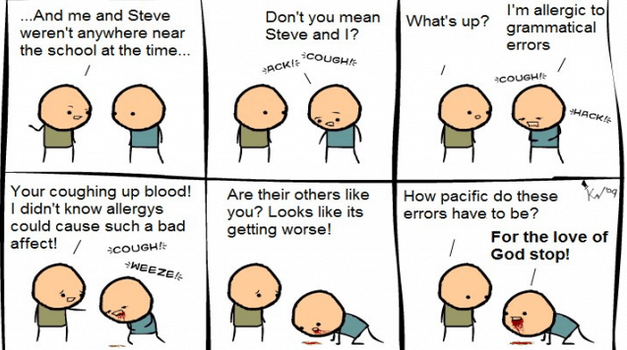

Facebook groups devoted to the use of good grammar are popular as well. Grammar Girl, for example, has nearly 206,000 likes; the Grammar Police has roughly 117,000 likes; finally, English Grammar, with 250,000 likes, appears to be the most popular of the grammar sites, perhaps thanks to its newsletter which promises readers will “Be the first to know when grammar rules change!” Can we really all be so interested in proper subject-verb agreement? Are grammar cartoons, or photos and screenshots of other people’s grammar mistakes that funny? Apparently—at least to the readers of these books and subscribers to these Facebook pages—they are.

Facebook groups devoted to the use of good grammar are popular as well. Grammar Girl, for example, has nearly 206,000 likes; the Grammar Police has roughly 117,000 likes; finally, English Grammar, with 250,000 likes, appears to be the most popular of the grammar sites, perhaps thanks to its newsletter which promises readers will “Be the first to know when grammar rules change!” Can we really all be so interested in proper subject-verb agreement? Are grammar cartoons, or photos and screenshots of other people’s grammar mistakes that funny? Apparently—at least to the readers of these books and subscribers to these Facebook pages—they are.

Grammar is comforting. There are right and wrong answers, accompanied by rules and explanations. That these rules are often arcane, the explanations often difficult to follow, makes grammar that much more appealing to a certain segment of the population. Grammar is the English major’s version of calculus: mystifying to those who don’t understand it, reassuringly ordered to those who do. Given that English majors, and others invested in the arts or humanities, are used to operating within a variety of shades of grey, it’s no wonder that grammarphiles feel so comforted by its black and white, its right and wrong.

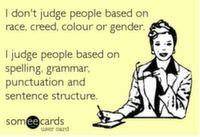

Unfortunately, it seems hard to love grammar without becoming a bully about it. Last fall, Slate published an interesting analysis of language bullies, emphasizing that their need to correct other people’s grammar or usage mistakes generally arises from a desire to assert their superiority, either over someone of a lower status (a YouTube commenter, for example) or someone who should know better (an editor at The New York Times). Ultimately, the article concludes, those who are secure in themselves will let these kinds of mistakes go rather than publicly correcting them.

Unfortunately, it seems hard to love grammar without becoming a bully about it. Last fall, Slate published an interesting analysis of language bullies, emphasizing that their need to correct other people’s grammar or usage mistakes generally arises from a desire to assert their superiority, either over someone of a lower status (a YouTube commenter, for example) or someone who should know better (an editor at The New York Times). Ultimately, the article concludes, those who are secure in themselves will let these kinds of mistakes go rather than publicly correcting them.

Despite being castigated as bullies, grammarphiles (often happily referring to themselves as “grammar Nazis”) continue to compile photographs of hilariously incorrect grammar, and to correct mistakes wherever they find them. Are they stewards of an English language under threat, or annoying pedants who should keep their corrections to themselves? Whatever we may think of them, clearly they—and our complex relationship to grammar—are here to stay.

Despite being castigated as bullies, grammarphiles (often happily referring to themselves as “grammar Nazis”) continue to compile photographs of hilariously incorrect grammar, and to correct mistakes wherever they find them. Are they stewards of an English language under threat, or annoying pedants who should keep their corrections to themselves? Whatever we may think of them, clearly they—and our complex relationship to grammar—are here to stay.

Are you a grammarphile or a grammarphobe? Let us know in the comments!

Image Credits:

Cover graphic: Cyanide and Happiness © Explosm.net

As a technical editor, I think this should be a national holiday!