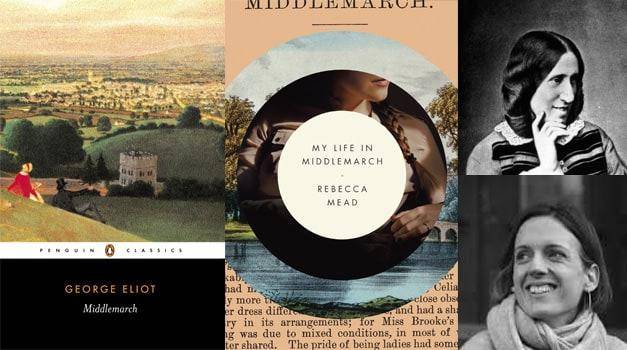

I retain only the vaguest impressions of George Eliot’s Middlemarch. I read it as a 19-year-old study abroad student in England, too busy exploring a new country and having my first romance to fully appreciate an 800-page treasure of literature. I certainly missed out on the life-changing experience with Eliot that Rebecca Mead, author of the recent My Life in Middlemarch, had as an English teenager in rural Dorset. Now 45 and a New Yorker staff writer, Mead has reread Middlemarch countless times, always gleaning new emotional and philosophical insights. Virginia Woolf famously called Middlemarch “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people,” and though Mead first met it as an adolescent, it has carried her through into grown-up life.

I retain only the vaguest impressions of George Eliot’s Middlemarch. I read it as a 19-year-old study abroad student in England, too busy exploring a new country and having my first romance to fully appreciate an 800-page treasure of literature. I certainly missed out on the life-changing experience with Eliot that Rebecca Mead, author of the recent My Life in Middlemarch, had as an English teenager in rural Dorset. Now 45 and a New Yorker staff writer, Mead has reread Middlemarch countless times, always gleaning new emotional and philosophical insights. Virginia Woolf famously called Middlemarch “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people,” and though Mead first met it as an adolescent, it has carried her through into grown-up life.

In her New York Times review of My Life in Middlemarch, Joyce Carol Oates calls this a “bibliomemoir,” a rather amorphous descriptor that nonetheless conveys the book’s essentially varied nature. Perhaps books like these do deserve a subgenre of their own, seeing as they combine so many different categories: literary criticism, memoir, biography, even travel narrative. In chapters whose titles echo the section headings of Middlemarch, Mead plots her journey into the book, weaving in archival research at libraries in Britain and America, details of Eliot’s unconventional life with her common-law husband, George Henry Lewes, discussion of the novel’s major themes, and visits to Eliot’s various homes in London and the Midlands (one is now a hotel; another is the Coventry Bangladesh Center).

Along the way Mead discovers that, in several peculiar respects, her life story mirrors that of her literary idol. Like Eliot, she found midlife love with a man named George and welcomed three stepsons; like Eliot, she left London to embrace a new place—though for Mead that meant crossing the Atlantic. Looking back from middle age, Mead can also see how her reading of the novel has changed over the decades. She used to identify most with Dorothea Brooke, the idealistic heroine trapped in a loveless marriage. Now she sympathizes more with Casaubon, Dorothea’s staid, scholarly husband, who is mired in an insurmountable project and whose heart has become as dry as his manuscript pages.

Along the way Mead discovers that, in several peculiar respects, her life story mirrors that of her literary idol. Like Eliot, she found midlife love with a man named George and welcomed three stepsons; like Eliot, she left London to embrace a new place—though for Mead that meant crossing the Atlantic. Looking back from middle age, Mead can also see how her reading of the novel has changed over the decades. She used to identify most with Dorothea Brooke, the idealistic heroine trapped in a loveless marriage. Now she sympathizes more with Casaubon, Dorothea’s staid, scholarly husband, who is mired in an insurmountable project and whose heart has become as dry as his manuscript pages.

Ever since Woolf and the Modernists, it has been unfashionable for novelists to intrude into their plots and cast moral judgments, but in the Victorian period such was commonplace. Indeed, Mead characterizes Middlemarch as a “masterwork of sympathetic philosophy,” teaching readers to grow out of self-centeredness into emotional maturity. “I have grown up with George Eliot. I think Middlemarch has disciplined my character,” she affirms.

Ever since Woolf and the Modernists, it has been unfashionable for novelists to intrude into their plots and cast moral judgments, but in the Victorian period such was commonplace. Indeed, Mead characterizes Middlemarch as a “masterwork of sympathetic philosophy,” teaching readers to grow out of self-centeredness into emotional maturity. “I have grown up with George Eliot. I think Middlemarch has disciplined my character,” she affirms.

Of course, there is an element of serendipity in any relationship with a beloved book. Mead believes that a certain book “can insert itself into a reader’s own history…until it’s hard to know what one would be without it.” As she admitted in a recent interview, “I don’t really know who I’d be if I’d chosen David Copperfield.”

Jane Austen is another popular subject for “journeys into the book” (a popular subject for anything, for that matter). I highly recommend two Austen-themed quests: All Roads Lead to Austen by Amy Elizabeth Smith, and Among the Janeites by Deborah Yaffe. Smith takes the rather unusual approach of transplanting Austen to Latin America, where she ran Spanish-language book clubs for eager readers who, in many cases, had never heard of Austen before. Encountering Austen’s books in this fresh way revealed what is truly universal about them: the humorous social observations and the everyday family and romantic dramas. Such topics translate into any language.

Yaffe’s book is a group biography of Austen’s fans—or, rather, diehard addicts. These devotees devour fan fiction, spend hundreds of dollars on custom-made corsets and gowns, and make pilgrimages to English heritage sites like Bath and Winchester Cathedral. It’s a whole new angle: understanding Austen through her enthusiasts.

Wendy McClure divulges her obsession for Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie series in The Wilder Life. In some ways it resembles a straightforward road trip narrative around the Midwest, with McClure, a children’s book editor, following the route the Ingalls family took on their pioneer wanderings between dugouts, sod houses, and prairie towns. Yet it is also a witty tour through Wilder’s books and their continued importance in McClure’s life, especially after the recent loss of her mother. (And, bonus: she even attempts butter-churning in her Chicago apartment.)

I loved each of these learned, all-encompassing tributes to cherished works of literature. Call them homages, call them bibliomemoirs; whatever the label, I call them delightful.

As Mead acknowledges, “all readers make books over in their own image.” This seems an inevitable part of assimilating a book into your intellectual and emotional life. To paraphrase Heraclitus, though, you can never step into the same book twice; we change, and our favorite books seem to change, as we age. Yet one thing is certain: a chosen book or author, once dear, will always be there for you. Some love affairs are just meant to be.