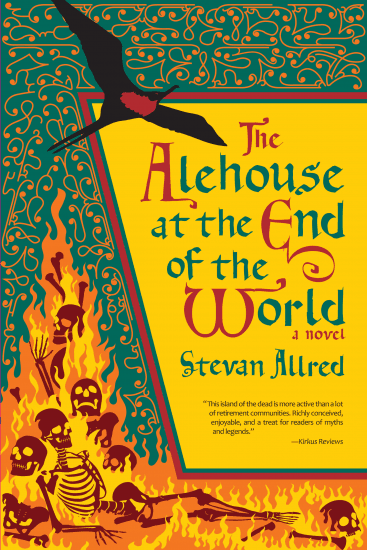

The Alehouse at the End of the World by Stevan Allred

A romantic quest, talking birds, and souls imprisoned in clam shells, The Alehouse at the End of the World (Forest Avenue Press) is as wild as it sounds. Stevan Allred has given us a tale that mixes fables, Shakespearean comedy, and a journey through the underworld that will make us question all our own far-reaching fantasies about the afterlife.

Mixing pop culture with myths passed on for centuries, this unique story follows a fisherman on a personal mission to reunite with his deceased wife in the Isle of the Dead. Without losing the tenacity of his original purpose, the fisherman takes on a whole new mission to save the undead world from being consumed entirely by the monster Kamah who reigns over it. Shapeshifting demigods delight readers and frustrate our hero on his path to saving the world.

For more on Stevan Allred’s inspiration for his twisting, hilarious novel and his own vision of the afterlife read BookTrib’s interview with him!

![]() BookTrib: The Alehouse at the End of the World reads as a fairytale for adults. What made you want to craft this kind of unique tale that revels in adult escapades but situates them in mythical lands and magical creatures?

BookTrib: The Alehouse at the End of the World reads as a fairytale for adults. What made you want to craft this kind of unique tale that revels in adult escapades but situates them in mythical lands and magical creatures?

Stevan Allred: A fairy tale for adults, a bedtime story for grown-ups, a hopeful tale for our troubled times–Alehouse is all those things and more.

Carol Shields (The Stone Diaries) once said “Write the book you want to read, the one you cannot find,” and that is great advice for a writer. As I began this novel I thought about books that I had loved my whole life through, books like Ursula LeGuin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, and it struck me that one thing I loved about them was the audacity of their creators’ imaginations, the way they took me places I had never been, and made those places as real as the world we all walk around in.

Once I had begun the work and the characters began to emerge, I let my invented demi-gods and their human companions drive the narrative forward. How would a sex-positive fertility goddess behave? If an everyman like my fisherman found his way to the afterlife how would he survive? What would a shapeshifting, über-compassionate pelican with a literally bleeding heart do when confronted with an implacable evil? I answered those questions in ways that entertained me, in the hope that what I found amusing would in turn amuse readers.

BT: How did you come up with the villain of the pompous yet calculating crow who possesses many of the same traits and abilities as a human?

SA: Just as actors will tell you it’s more fun to play the villain than it is to play the hero, it’s way more fun to write the villain. I didn’t so much write the crow as let the crow write me, which is to say I turned off all my social filters and let the crow be the narcissistic, self-aggrandizing bully he is. I ‘played’ him as a being who is all avarice and id, someone who has come to power after a long time of being ignored, and who is bent on reshaping the world into his own private toy. I allowed him to do things most of us would never do in real life. He is appalling, and yet he has a story to tell about what it’s like to be treated as an insignificant underling for way too long, and how that makes one behave when one does finally gain power.

BT: The general structure/archetype of your story is the Hero’s Journey, but more specifically it is a mix of many heroes and fables. Jonah and the whale, Orpheus’ quest to the dead for his beloved, and numerous mythologies are featured in a sort of Shakespearean comedy. What was your writing process like and how did you choose which myths to integrate or create in the fisherman’s journey?

SA: I was raised LDS, and I read The Book of Mormon when I was 16 or so. By then I was already questioning my faith, and I came to think of The Book of Mormon as the biblically-informed, wildly creative fever dream of Joseph Smith. Mormons believe The Book of Mormon was translated from hieroglyphics on golden plates by Smith, acting under divine supervision from God, but I understand it as one more cosmology amongst many that humans have invented in order to understand their place in the universe.

I’m very much a secular humanist, I’m a fiction writer, and I’ve got this personal history with Mormonism I’ve just described. I grew up reading The Chronicles of Narnia, Tolkien, and a lot of science fiction, and I’ve always been fascinated by mythology. It wasn’t a big stretch for me to invent an afterlife with its own complete cosmology; rather, it was something I had always wanted to do.

As to which myths I chose to incorporate into The Alehouse at the End of the World, I gave myself a free hand to throw in a little of this and a little of that. Joseph Campbell was a huge influence, and his notion that there is certain mythology that keeps surfacing throughout all time and all cultures was, for me, permission to take a collagist’s approach to my invented cosmology. That approach became one of the more beguiling aspects of writing Alehouse. And you just can’t go wrong stealing from Shakespeare.

BT: Within the fisherman’s own quest to find and restore his beloved is a larger one to prevent the Kiamah beast, the enormous master of the Isle of the Dead, who is an accumulation of all the evil souls lost in the War of the Gods, from devouring all. What kind of an eternity do you picture personally? One with the Kiamah reigning, or a more friendly version?

SA: I’m either an atheist, an agnostic, or a nontheist, depending on how you define those terms and on how I’m feeling at any given moment. I like rational explanations for the natural universe and how it works. I get skeptical pretty fast when someone says I have to have faith in something unprovable in order to accept their cosmology.

If there is a god, and if we do have actual souls, then I think that the universe is itself that god, unimaginably large and of such an age as to seem like eternity. If that universe, that immeasurably large ‘god’, has consciousness, then when I die my personality will die with me, but whatever piece of me is my soul will return to that larger consciousness as a drop of rain returns to the sea.

The more likely explanation for me is that we are born, we live, and we die, and that’s it. No afterlife, no reincarnation, no such thing as god or heaven or hell or devil. These things are better understood as metaphors for how we experience life than as objective realities, and it was in that spirit that I wrote The Alehouse at the End of the World.

BT: If you could pick any three individuals from books or pop culture to accompany yourself on your own quest in the Isle of the Dead, who would you choose and why?

SA: Sorry, I need four individuals to do this justice:

-Samwise Gamgee, from The Lord of the Rings, because Sam is always good company, he is fundamentally intrepid, and he’s not one to miss a meal.

-Gandalf, also from The Lord of the Rings, because he is a wise, far-seeing, totally bad-ass wizard, and he has the best fireworks ever.

-And both Thelma and Louise from the eponymous film, because they’re smart and funny and not afraid to die.

BT: What is one message or key aspect you hope readers take from the story when they finish?

SA: We’re facing an evolutionary crisis. We’re about to find out whether or not these big brains we all have are a successful adaptation. We have all this amazing technology, a lot of which makes our lives better, and yet we’re cooking the planet because we can’t seem to think beyond the next few months, let alone the next few generations. And we are doing a very poor job of distributing the benefits of modernity equally to all peoples.

We cannot give in to despair. The Alehouse at the End of the World is a story about a small band of heroes who stand up and stand together for the best in humanity, instead of succumbing to those who pander to the worst.

BT: What authors or books would you say most influenced you as a writer?

SA: Alice Munro, for her deep understanding of character and circumstance, and her consummate ability to pack so much humanity into a story. Michael Chabon, for his prodigious gifts as a prose writer, and for showing us that genre fiction can be great literature. Ursula LeGuin for the breadth and perceptiveness of her vision, and for her fierceness in speaking truth to power. Frank Herbert’s Dune, for the breadth and inventiveness of its vision. Tom Spanbauer, because he taught me how to be a writer. Annie Proulx, for her exquisite ability to capture a place and the people connected to it.

BT: Current project?

SA: I have a lot of notes for a sequel to Alehouse, but I won’t start writing until all the fun of launching this novel fades a bit.

BT: What is one question you always wish you were asked?

SA: What was your earliest influence as a writer?

Answer: Mrs. Bumgardner, my 5th grade teacher, gave the class a creative writing assignment–my first ever. I loved Mrs. Bumgardner, and when what I wrote made her laugh, she had me read it to the whole class. I was hooked right then, and making Mrs. Bumgardner laugh was the job I wanted when I grew up.

Buy this Book!

Amazon