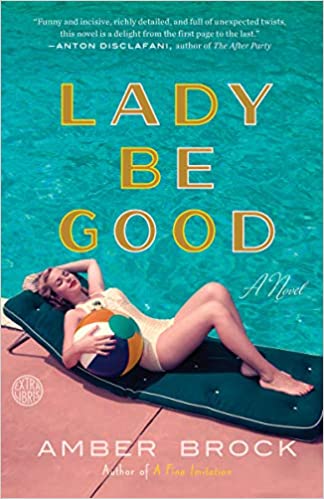

Lady Be Good by Amber Brock

In 1924, George and Ira Gershwin wrote one of their most famous songs:

I am so awf’ly misunderstood

So, lady be good to me. . .

The heroine of Amber Brock’s Lady Be Good is indeed a misunderstood young woman, tormented by desires both frivolous and serious. Beautiful and wealthy, the only daughter of a hotelier whose money is unacceptably nouveau, Kitty Tessler devotes much of her time to figuring out how to be welcomed into New York City’s Knickerbocker crowd. Her friendship with a former schoolmate Henrietta (“Hen”) Bancroft, whose patrician family is listed in the social register, has not yielded the entrée she craves.

It is 1953 and American culture and society have been upended in the postwar world. Thus it is intriguing to find Kitty longing for acceptance much like the women who were excluded from Mrs. Astor’s 400 during the late nineteenth century, a strict old-money crowd. Yet as the story unfolds in Manhattan, Miami, and Havana, the reader comes to understand that Kitty’s world is as provincial as the one she longs to join. Ultimately, Kitty liberates herself and Hen from the constraints of convention and stereotypes.

It is 1953 and American culture and society have been upended in the postwar world. Thus it is intriguing to find Kitty longing for acceptance much like the women who were excluded from Mrs. Astor’s 400 during the late nineteenth century, a strict old-money crowd. Yet as the story unfolds in Manhattan, Miami, and Havana, the reader comes to understand that Kitty’s world is as provincial as the one she longs to join. Ultimately, Kitty liberates herself and Hen from the constraints of convention and stereotypes.

Kitty triumphs through a complicated plot that includes Hen’s repressive mother, Kitty’s adoring papa, the cheating son of aristocrats to whom Hen is engaged, two musicians – one Cuban, one Jewish – and Kitty’s father’s right-hand man. These characters engage with each other in frustration, desire and delight; meanwhile, the romances bloom. And amidst the gorgeous dresses, cocktails, and sumptuous bar lounges, it is intriguing to find the novel’s theme, derived from a poem by T. S. Eliot, “Little Gidding”: “. . . to make an end is to make a beginning. The end is where we start from.”

It’s clear that the author Amber Brock put an immense amount of research and thought into crafting such vibrant and authentic characters. To better understand her creative process and how she was able to resurrect the overlooked tensions of the 1950s with such success, we interviewed Amber Brock, author of Lady Be Good.

Claudia Keenan: Was there any particular inspiration for the novel?

Amber Brock: I often find the seeds of new ideas as I’m listening to music in my car on the way to or from work. One day, I was listening to Annie Lennox’s “Walking on Broken Glass,” and I had a crystal clear image in my mind of the girl who would become Kitty, platinum blond hair and all. Later, as I was fleshing out the initial story idea, my agent regaled me with some wild stories about a society maven who had grown up in a hotel. I added in elements of those stories, and Lady Be Good was officially born.

CK: Why did you choose to set the book in 1953?

AB: A lot of Americans think of the Fifties as a golden era of peace and prosperity, but that’s only true for certain segments of the population. I was drawn to the conflict that simmered under the surface and eventually led to the radical social change of the 60s that continues to the present day. I was especially interested in the fact that these changes weren’t a uniquely American phenomenon—Cuba had its own unrest that would boil over in the Sixties in a different way.

There was also a glamour to the era that was an appealing contrast to the turbulence. That dichotomy is an important part of the push-and-pull of Kitty’s journey. She wants the high life precisely because it will shelter her from certain troubles, but she comes to recognize that there are important pieces of her life she’d have to give up in exchange for that security.

CK: Do you feel Kitty resembled Scarlett O’Hara as a scheming, beautiful young woman trying to move people around as if they are chess pieces?

AB: I love that comparison, and it’s so apt. Kitty has a fire in her, like Scarlett, and they both believe they’re doing what’s best. In Kitty’s case, she does at least have her friend’s best interest in mind, although she’s dead wrong about what her friend actually wants, and her confrontation with that mistake is at the heart of Kitty’s growth. I was inspired by Jane Austen’s Emma as I created Kitty: another headstrong, clever protagonist who can be blind to others’ needs while still harboring good intentions. And all three of those characters make a huge mess for themselves at one point or another!

CK: Among the great details that you include, the portrayal of the men and women of the social register and their distaste for ruthless social climbers really stands out. How did you research that aspect of New York City history?

AB: I did a good deal of research on that social tension for my first novel, A Fine Imitation, and it truly is a conflict that is evergreen. I read articles about the exclusive clubs in New York City and the socialites that populated them, including Babe Paley and Slim Keith (and, even at her exalted level, Paley had to contend with anti-Semitism). There’s always a small group at the top of society that relies on keeping that group exclusive to maintain their status. For New York City, in particular, that emphasis on “in” versus “out” remains important. In the first half of the twentieth century, the focus of the exclusivity shifts slightly from heritage to inheritance, but the song remains the same. At its heart, status is always about money and the prestige it buys. Kitty, in aspiring to that world, fails to see what it costs.

CK: Similarly, the scenes set in pre-revolution Cuba are quite evocative. Did you interview people who lived in Havana during that time?

AB: Part of my studies in both college and graduate school focused on Cuban culture and history, and I count the children and grandchildren of Cuban immigrants among my friends. For the scenes in Lady Be Good, I relied on both non-fiction historical accounts of the pre-revolutionary era (including Havana Before Castro by Peter Moruzzi and Havana Nocturne by T. J. Miller, for anyone looking for compelling further reading). I also have a librarian in the family who tracked down several oral histories, both of Cuba in the 1950s and the two decades before. We have a view of Cuba in the U.S. that is colored by our political relationship with that country in the 20th century, and that can cause bias. I wanted to take care that my research represented a nuanced view from the people who’d actually lived in that world, and the oral histories (even when they conflicted) were enormously helpful with that aspect.

CK: Kitty’s revelation of how the other half lives seems to flow from T.S. Eliot’s beautiful poem, “Little Gidding.” Did you plan from the beginning to use an excerpt from the poem?

AB: Yes, from the very beginning! “Little Gidding” is my favorite poem, so it was inevitably going to feature in one of my novels. In the earliest stages of planning Lady Be Good, I sat down with the poem and hand wrote every line that I felt resonated with the story I wanted to tell. Even when I only knew a few details about Kitty and her life—her aspirations, her family’s background, and her transformative experience—I knew the thematic elements of the poem would underscore her journey. Even after multiple edits and the natural evolution of the novel from concept to finished product, those elements are still there. The poem was a perfect fit. The only lines that I didn’t end up including were “History may be servitude/History may be freedom,” because I felt like those words didn’t belong to any one single chapter. They sort of hover over the whole story and all the characters’ lives.

CK: Ultimately both Kitty and her best friend, Henrietta (“Hen”), fall in love with men who are nearly the opposite of the types that their parents hoped for. Did you set out to write a novel that would illuminate the changing culture of the early 1950s?

AB: I teach at a girls’ school, so my students are always in the back of my mind when I write. Because of that, I like to focus on the ways evolving social climates affect the lives of women. I want my students to see how things have changed and (perhaps even more so) how they haven’t. But no matter what the norms of a given era, change always begins with individuals choosing a different path than the one society dictates, even in small ways. In the end, Kitty especially goes against the convention of the time with the direction she sees her life taking.

Lady Be Good will be available for purchase June 26.